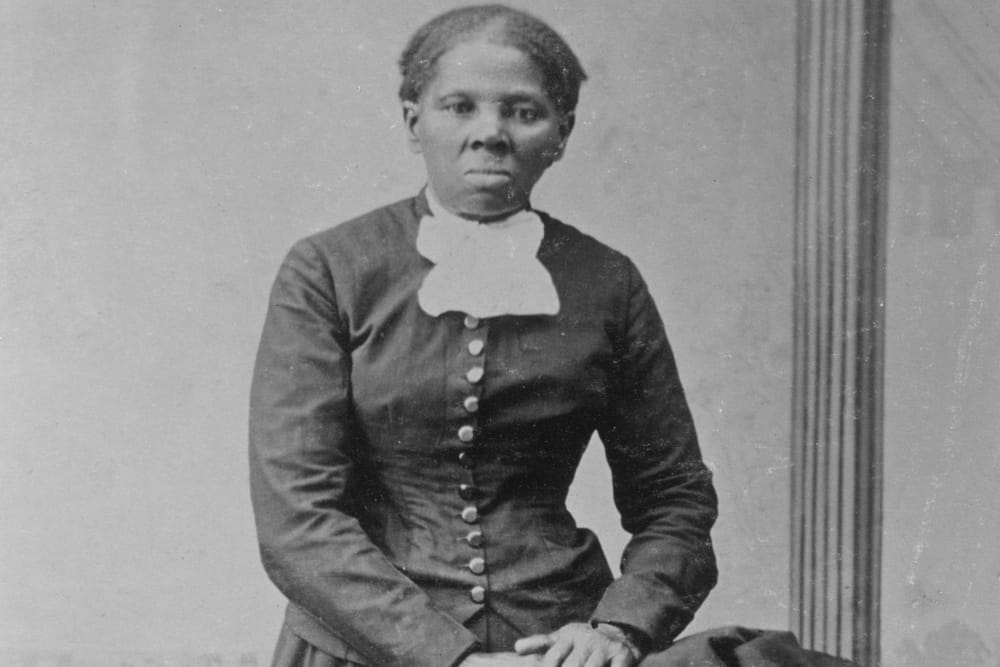

Harriet Tubman is best known as a conductor on the Underground Railroad. She was born around 1820 on a plantation in Dorchester County, Maryland. Her parents, Harriet (“Rit”) Green and Benjamin Ross, named her Araminta Ross and called her “Minty.”

Harriet had eight brothers and sisters, but they were soon split apart despite Rit’s attempts to keep the family together. When Harriet was five years old, she was rented out as a nursemaid, where she was whipped when the baby cried, leaving her with permanent emotional and physical scars. Around age seven, Harriet was rented to a planter to set muskrat traps and later rented as a field hand. Harriet preferred physical plantation work to indoor domestic chores.

When Harriet was twelve, she spotted an overseer about to throw a heavy weight at a fugitive. Harriet stepped between the enslaved person and the overseer — the weight struck her head.

“The weight broke my skull … They carried me to the house all bleeding and fainting. I had no bed, no place to lie down on at all, and they laid me on the seat of the loom, and I stayed there all day and the next.” — Harriet Tubman

Harriet’s injury left her with headaches and narcolepsy for the rest of her life, causing her to fall into a deep sleep at random. She also started having vivid dreams and hallucinations, which she thought were religious visions.

In 1840, Harriet’s father was set free, and Harriet learned that Rit’s owner’s last will had set Rit and her children, including Harriet, free. But Rit’s new owner refused to recognize the will and kept Rit, Harriet, and the rest of her children in bondage.

Around 1844, Harriet married a free Black man, John Tubman, and changed her last name from Ross to Tubman. The marriage was not good, and when she learned that two of her brothers — Ben and Henry — were about to be sold. Harriet planned an escape.

On September 17, 1849, Harriet, Ben, and Henry escaped their Maryland plantation. Her brothers changed their minds and went back. With the help of the Underground Railroad, Harriet persevered and traveled 90 miles north to Pennsylvania and freedom. Tubman found work as a housekeeper in Philadelphia, but she wasn’t satisfied living free on her own — she also wanted freedom for her loved ones and friends.

Harriet returned to the South to lead her niece and her niece’s children to Philadelphia via the Underground Railroad. At one point, she tried to bring her husband John North, but he’d remarried and chose to stay in Maryland with his new wife.

The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act allowed fugitive and freed workers in the North to be captured and enslaved. This made Harriet’s role as an Underground Railroad conductor much more complicated and forced her to lead enslaved people further north to Canada, traveling at night, usually in the spring or fall, when the days were shorter. She carried a gun for both her protection and to “encourage” her charges, who might be having second thoughts. She often drugged babies and young children to prevent slave catchers from hearing their cries.

Harriet personally led at least 70 enslaved people to freedom, including her elderly parents, and instructed dozens of others on how to escape on their own.

“I never ran my train off the track, and I never lost a passenger.”

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Harriet found new ways to fight slavery. She was recruited to assist fugitive enslaved people at Fort Monroe and worked as a nurse, cook, and laundress. Harriet used her knowledge of herbal medicines to help treat sick soldiers and fugitive enslaved people.

In 1863, Harriet became head of an espionage and scout network for the Union Army. She provided crucial intelligence to Union commanders about Confederate Army supply routes and troops and helped liberate enslaved people to form Black Union regiments.

On June 1, 1863, the Raid on Combahee Ferry made Tubman the first American woman to oversee military action in a time of war. Using information gleaned from her spy network, Tubman worked with Colonel James Montgomery to free more than 750 men, women, and children from enslavement on the rice plantations along the Combahee River.

After the war, Tubman struggled to collect compensation for her military service. In a pension application filed around 1898, she described her three years as a “nurse and cook in hospitals” and as “commander of several men (eight or nine) as scouts during the late war of the rebellion.” At the time, she was receiving only a small pension as the widow of Union veteran Nelson Davis. But in 1899, Congress passed legislation that raised Tubman’s pension to $20 a month for her work as a nurse, which she received until she died in 1913.

Officials in the abolitionist’s home state honored her military service during the Civil War at a ceremony on Veterans Day.

“Harriet Tubman lived the values and virtues that I was taught when I served in the United States Army, and many of the people here today learned too: Live mission first, people always. Lead with honor, integrity, duty, and courage. Leave no one behind. And with each act of courage, Harriet Tubman helped bring us together as a nation and a people. She fought for a kind of unity that can only be earned through danger, risk, and sacrifice. And it is a unity we still benefit from to this day.” — Maryland Governor Wes Moore

After serving in several military roles, mainly as a volunteer, Harriet Tubman was posthumously recognized as a one-star brigadier general in Maryland’s National Guard.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Garrick McFadden's work on Medium.