Jewish teens Jerome Siegel and his artist friend Joe Shuster created the character Superman in 1933, the same year Hitler came to power. (In case you were still wondering if anyone knew what Hitler was about before the Holocaust).

These young adults birthed the character to fight the growing threat of fascism and Nazism. Superman was their symbol of hope over oppression.

For decades, many superheroes were symbols of the hard fight against hatred and bigotry. That’s waned in recent times, but about a decade ago, a new comic book-graphic novel, “Concrete Park,” found a renewed way to tackle the hardest racism to fight.

The unconscious type living deep within us. The kind that infects everyone. Even the most well-intended people.

To understand how “Concrete Park” got here, it’s important to know the history of comic heroes.

Although the comic company, Action Comics, barely paid the young adults for the rights to Superman (and today the companies still haven’t paid reparations to their descendants), the original Superman character spawned generations of more superheroes to fight injustice.

In the 1970s, The Green Lantern and Green Arrow characters teamed up to tackle injustice and social issues. The two heroes addressed racism, poverty, oppression, and drug abuse.

Captain America punched Nazis after World War II began.

In one comic, Superman grabbed Hitler and Stalin by the necks and imprisoned them at the League of Nations headquarters for punishment. Superman single-handedly ended World War II before America ever got involved.

Superman later took on the Ku Klux Klan, and Batman made public service announcements denouncing racism against Black people.

Spiderman once fought against drug use and addiction.

There were other, lesser known comic book heroes who fought for civil rights and equality in the 60s despite the government’s attempt to investigate the harmful effects of comic books on kids.

A familiar story of politicians deflecting blame on others for their ineptitude. Oh, those dangerous comics.

Since those injustice-fighting days, comic book heroes for the most part are more subtle now. Most Marvel superheroes live in New York. Not many have been busy taking out Bin Laden, Hezbollah, Putin or other world dangers.

Rarely do many modern superheroes protest police brutality. Or other forms of racial injustice.

The days of tackling racism in America. Or Islamophobia, homophobia and the umpteen number of other xenophobic maladies. Or the ever-increasing antisemitism on college campuses and around the globe. Those battles have all but disappeared as the central theme in comic books.

Enter “Concrete Park.”

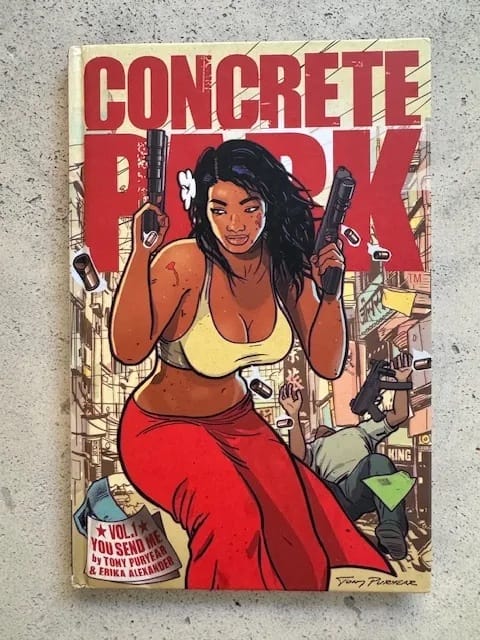

First launched a decade ago by “In Living Color” star Erika Alexander, it’s a science fiction story about a prison planet where Earth’s poor and marginalized have been deported for slave labor in frozen mines. Gangs form on the prison planet and the story takes off from there.

Like earlier justice comics, the graphic novel deals with racism and poverty. But how “Concrete Park” truly fights modern-day injustice is nothing short of brilliant.

It features Brazilians, Africans, Black Americans, Chinese, Indians, Latin Americans and other “minorities” whose individual cultures and voices each stand loud in the story, often showcasing how they interact in ways that are profound yet nuanced.

The characters aren’t background. They are the story in all their glory.

On top of that, women play central roles in the story, including being the bad asses among the lot of characters.

Here’s the trap “Concrete Park” so cleverly avoids:

We’ve all been conditioned and taught to learn certain biases about people.

What your doctor is supposed to look like. Or your dentist, lawyer or accountant. We have ideas in our heads about what ethnic group is supposed to work our farms. Or who is smart or capable. Who is wealthy and who is poor. Who invents our technology.

We’ve been fed ideas about what criminals look like. Or athletes, bankers and even first responders. We easily conjure up an identity of who the world’s so-called puppet masters are.

I don’t even need to say their names since you know exactly what I’m talking about.

“Concrete Park” does something extraordinary to undermine these ingrained biases and stereotypes.

The purpose of all of Concrete Park’s multi-ethnicity isn’t part of some great replacement theory. To rid our world of white heroes. I think you’re safe on that front.

It’s deeper than that.

It’s to teach us a hard truth that’s been avoided for centuries.

That people from every race, ethnic group, religion, gender or identity also can and should also be our heroes. They can be our doctors and lawyers. They can be brilliant or dumb. That can be soft or angry. Kind or mean. They can be capable or not. They can be good Samaritans or criminals.

The only way for us to unravel generations of well-trained bias is to start seeing others in a non-racist, fairer and more accurate light.

As the wide range of humans we all are.

The real news can be a bit overwhelming these days. Teens and young adults especially can easily feel as though there isn’t much hope.

That’s why “Concrete Park” is needed more than ever.

Its roadmap to freedom and prosperity is a beautiful reminder that while none of us can control everything around us, especially right now, we can all proceed in life with the confidence that though the past and present may be painful, as Alexander put it, “the future is free.”