In America, civil rights legislation has become a double-edged sword. Meaning laws that shield racial minorities from harm are also used against them. Take, for instance, the attack on race-based affirmative action policies. Lawyers argued that considering applicants' race violated the "equal protection clause." They overlooked the purpose of these programs, which was leveling the playing field. Once stripped of context, they portrayed hierarchy-attenuating programs as reverse discrimination. This argument was convincing to the conservative-leaning Supreme Court. In the aftermath, the rate of Black student enrollment dropped. Some may ask why this argument matters. After all, race-based affirmative action policies are now banned. Yet, this is bigger than any one policy or program. Their approach revealed a strategy with a broad application of using civil rights legislation to halt racial progress.

The allegation of "reverse discrimination" isn't new. An 1867 Union Springs article, Negro vs. White Labor, dispels any notion that it was. Despite most Black people suffering in poverty, the author portrayed them as privileged. Give white men "an equal chance with the negro," they pleaded without a hint of irony. They sprinkled in various racist insults to justify their worldview. Calling Black people "a class proverbial for their ignorance, indolence, and dishonesty." The root of his complaint was that too many job contracts required white men to have Black partners. Since they were the primary laborers for centuries, this was common practice. They claimed that "poor whites" only existed because Black people took their jobs. Society needed to "destroy this prejudice and discrimination against white labor," they insisted. Yet, the facts at hand expose the absurdity of this claim. Slavery deprived Black people of pay for their labor. And black codes blocked their descendants' upward mobility. Today, they earn less than any other racial group.

We must remember the order of operations. That racism made civil rights protections and legal remedies necessary. Not the other way around. An 1866 Richmond Examiner article highlighted early resistance to civil rights legislation. Editors referred to the 14th Amendment to the Constitution as "an insult to the South." They were speaking, of course, of the dissatisfaction of many white citizens. The federal law established birthright citizenship and equal protection for Black people. And historical evidence suggests many struggled to cope with the social shift. For instance, Democratic politician Alexander Stephens called the legislation a "gross usurpation of power." As a former Confederate, it should come as no surprise that he opposed civil rights legislation. Along with white domestic terrorist groups, many politicians sought to disempower Black people ahnd restore the system of white supremacy. Thus, removing legal support for racism was only half the battle. The other half would be mitigating hundreds of years of discrimination.

Affirmative action policies are one example of an effort to level the playing field. However, by that same measure, diversity, equity, and inclusion play a similar role. They seek to mitigate racism and other forms of discrimination applicants endure. They are hierarchy-attenuating programs. Contrary to popular belief, they don't promote granting unqualified people opportunities. They extend them to talented people who are, too often, overlooked. Many struggle to acknowledge the racism Black people experience. Or that merit alone is not enough to overcome this impediment. A 2008 article in the Annual Review of Sociology highlights this dilemma. Researchers commented that the nation has made "great progress" since the 1960s. But, "racial discrimination" helps to shape "contemporary patterns of social and economic inequality." Alleging reverse discrimination has proven effective in diminishing support for hierarchy-attenuating programs. And yet, it doesn't change that they're needed to level the playing field.

Kwame Ture, the Black civil rights leader, once said, "racism is not a question of attitude; it's a question of power." Sadly, claims of reverse discrimination overlook this distinction. And we will likely see this trend of exploiting civil rights legislation continue. This is because of the language of equality. For instance, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 declared that those born in the U.S. were citizens. And established they had "certain inalienable rights, including the right to make contracts." For the first time, Black people could "own property, to sue in court, and to enjoy the full protection of federal law." This "equality" was also affirmed in the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause. Again, in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, they declared citizens "equal," and established a new standard for society. Black Americans continued to endure racial discrimination. But, it would no longer be legally acceptable.

According to law professor David Weisenfield, this strategy isn't going anywhere anytime soon. He predicted that "reverse discrimination" cases would rise under the second Trump term. Mainly to attack the use of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. One example of this taking shape would be the federal appeals court ruling against the Fearless Fund. This grant program allocated funds to some Black women. Since they faced a higher rejection rate than White women, they sought to close the gap. But, a federal appeals court claimed this program violated "section 1981 of the 1866 Civil Rights Act. The law prohibits discrimination based on race when enforcing contracts. And thus, by trying to help Black women, they were accused of discriminating against a White woman. She never even applied for the grant or received a rejection letter. But that didn't stop her from blaming the group for discrimination. White people were never enslaved in this country. Nor were they treated as second-class citizens. Yet, white grievance politics has caused many to see themselves as victims. Rather than promoting racial equality, some use the legislation to roll back progress.

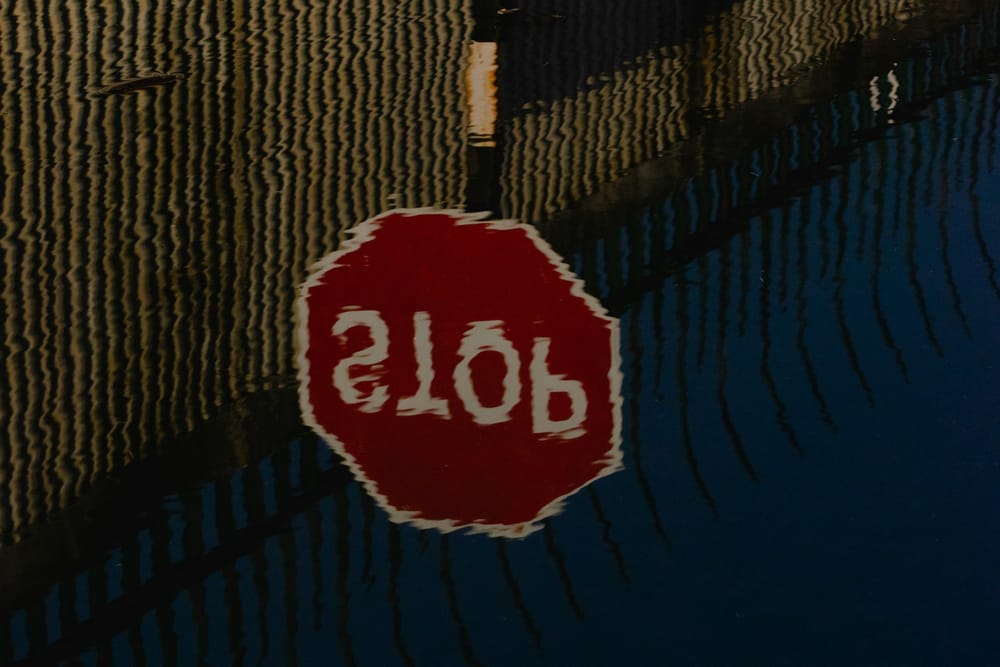

If you walk in during the middle of a conflict, it may be challenging to identify who swung the first blow. This is especially true without context. To muddy the waters, someone can remove key details about the story, such as how it started. And you may find yourself rooting for the aggressor. This is precisely the approach taken by those justifying the removal of programs that promote racial equity. Using civil rights legislation to halt racial progress is like salt in Black Americans’ wound. And yet, far too many Americans claim that the actions taken to level the playing field are unfair. Some may be uneducated about why the nation needed to take affirmative action toward remedying racism. At the same time, others are being disingenuous in their accusation, like White Southerners after the Civil War. Either way, this position is halting racial progress and preventing us from living in a nation where citizens are truly treated equally.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Dr. Allison Gaines' work on Medium.