I called my best friend Anwar in November of 2020 to deliver the news and come up with a plan. He is a fitness expert, by any measure, but his most official credential is his body, near 40 and as chiseled as he’s ever been. Most of the men I know, especially after kids, surrender to gravity’s droop. Not him.

He has spent 6 years carving his body, especially after having his first son. Something about his dedication to staying fit feels both rigorous and desperate. As I’m scrounging for my own sense of desperation, for ways to find it in a year when desperation needs my attention in so many other places, I know dialing him will help the mission. No sooner than I start to mention dietary changes as the baseline does he start rattling off facts about ‘macros’ and ‘lipids’ and ‘gluten reactions.’

There’s a difference between looking fit and being healthy, and he lives in that Better Wellness nation-state, striving toward greater health instead of ticking off new gym routines or bookmarking YouTube videos. He courts obsession and buys courses on bio-hacking (the new art of trying to live longer or live forever or live pain-free). He told me about his morning routine, wherein he drinks a liter of alkaline water. That is a trigger word for me after trying the Dr. Sebi diet in 2018 and losing 21 fast pounds off the principle that some food had the right neutrons or electrons and the other foods were dead. Rastas use a similar concept to cut out all the tasty foods that I like to eat. They call it ‘livity’, and somehow, salt is one of the flavors not included in living food even though it makes my tongue dance and my heart rate pump at unhealthy speeds. He said I should not eat grains, not even oats, to start the day.

To cut weight and to build muscle that burns fat, I would need to treat my body like a machine, specifically an engine, looking for efficiencies where now there was only fat and sluggishness. My best friend has the same birthday as , and I can’t help but wonder whether that’s the reason they share this militant belief about bodies and how they need to work. I cannot keep up with that stringency, but my weakness is probably that I wasn’t meant to anyway. The exercise regimen that we review seems to work. I already talk about exercise and the most efficient ways to build muscle, so I can spew facts about time-under-tension, recovery, cardio sprints mixed with rest days, flexibility, the miraculous results of simple motions like push-ups and pull-ups, the ways resistance bands can change and improve those motions, and all of the in-between knowledge that a YouTube nut might know offhand. The exercise hasn’t ever been the biggest challenge (even though I will take any tips he has on sustaining it). He reveals to me that he hasn’t been as strict about the exercise part this year since mastering the diet. That tracks with other information I’ve read and some of my own experience.

It feels weird to tell him that I’m doing this story so I can take nudes and turn this into a “moment” on the internet. A part of my life will (finally) become clickable. I know how to play the audience for the largest effect, and it will involve dispatching embarrassment about my skin once and for all. Forget the fact that I go to nude beaches, write about my romantic life, and overshare about politics. This is the one.

So I start texting my writer friends with only the title of the piece in the text. I’m using the name of a popular social site for sex workers because it’s a keyword. There is a difference between being unashamed and foolish, between being unpretentious and unpreposessed, and I’m making sure that it doesn’t seem clear I know the difference when blurting my idea. “30 pounds” is in the title for a while. “40 pounds” once. I wonder why I thought it would be possible for my 198-pound frame to lose forty pounds without suffering a terminal illness or ingesting a parasite. I have a secret obsession with the show “Alone” on The History Channel. The contestants have to survive a solitary wilderness mission with only a few tools. Some lose so many pounds they have to be medically evacuated for fear they’ll do irreversible damage to their organs with the extreme weight loss. The same is true of “The Biggest Loser,” whose contestants have often struggled with internal health as the show sunsets deep into their past. The human body isn’t designed to lose these amounts of dense weight. But we can try. So I spend the year trying.

Lesson 1: Listen to music during exercise to stay motivated.

Morning regimens are everything: I already feel bad when I don’t wake up by 7 a.m. The exercise routine is now tagged with that guilt. I have downloaded an app called “Seven,” which breaks the intense calisthenics into 7-minute blocks that I then repeat. In the workout world, we call that HIIT, and it’s supposed to be the most effective way to burn fat and build muscle. At least that is what my YouTube and Pinterest algorithms say. I am dripping, cranky, and hopeless when I begin these 25 to 30-minute sessions in November of 2020. Around January, that changes because I’ve found a rhythm, quite literally, through playlists. I go through four playlists on the Jeff Bezos-owned service where I subscribe and let a device track my habits, so I can maintain the convenience of giving it voice commands. They are called “Classic Soul Workout,” “R&B Workout,” “90s Hip Hop Workout,” and “Alternative Hip Hop Workout.” A few months in, I’ve narrowed the playlist selections to “R&B” and “Classic Soul,” taking unique, rejuvenating pleasure in Beyonce’s “Blow” and Ray Charles’s “Hear What I Say” until I forget I’m in a body roiled by flab and excess. (“Alexa: repeat the song” leads to “Okay, I’ll repeat the song,” and she’ll play it ad infinitum if I let her.) I love to forget. I don’t want to be in the fight that I’m in with my flesh.

Lesson 2: Find encouraging peers.

My stripper friend cannot live a moment without pills or skip a day of working out and berating herself. That’s about as much as we have in common. We are also both (bad) poets. I have a sick fantasy that I am a rapper unrealized and that, in another life, she’d fall in love with my riches and bravery. In reality, we are uneasy friends and unloving lovers. She inspires me.

Lesson 3: Surrender to the machines.

Automate your processes; employ robots: I wear an Apple Watch, which links to the Seven App, and takes my current calorie count to the meal tracker MyFitnessPal. Between months two and four, I have acclimated myself to weighing protein, and carbohydrates. I am calculating calories and getting an estimate of the food I ought to eat in order to reach my then-30-pound goal. I have a digital food scale that’s for dry-measuring baking ingredients. Now I’m using the black-and-silver analog display to dole out spoonfuls of quinoa and cauliflower, deftly removing a cluster at a time to shift the caloric result flashing on the screen. The MyFitnessPal app comes from a responsible company, and once I enter the goal weight, it programs my nutrition so that I can only lose so many calories in a given time span. In fact, it won’t log my caloric intake on single days when I don’t reach the minimum recommended calorie count for an adult my weight and height. Instead, I get a warning about low intake. When the program works how I like, I see an estimated weight. “If you eat like you did today for [five] weeks, you’ll weigh 181.5 in 5 weeks.” That’s all the motivation I need through January and February. I see abdominal muscles and biceps and my calves turning sharper. I still see the softness but less of it. Soft and sharp at war in my belly and with no clear victor after 9 weeks of training consistently. I have to automate burning the fat and the need to reach a goal each day. The Apple Watch becomes the central figure in this drama, especially its rings. I cannot go a day without closing my rings.

Lesson 4: Obsess carefully.

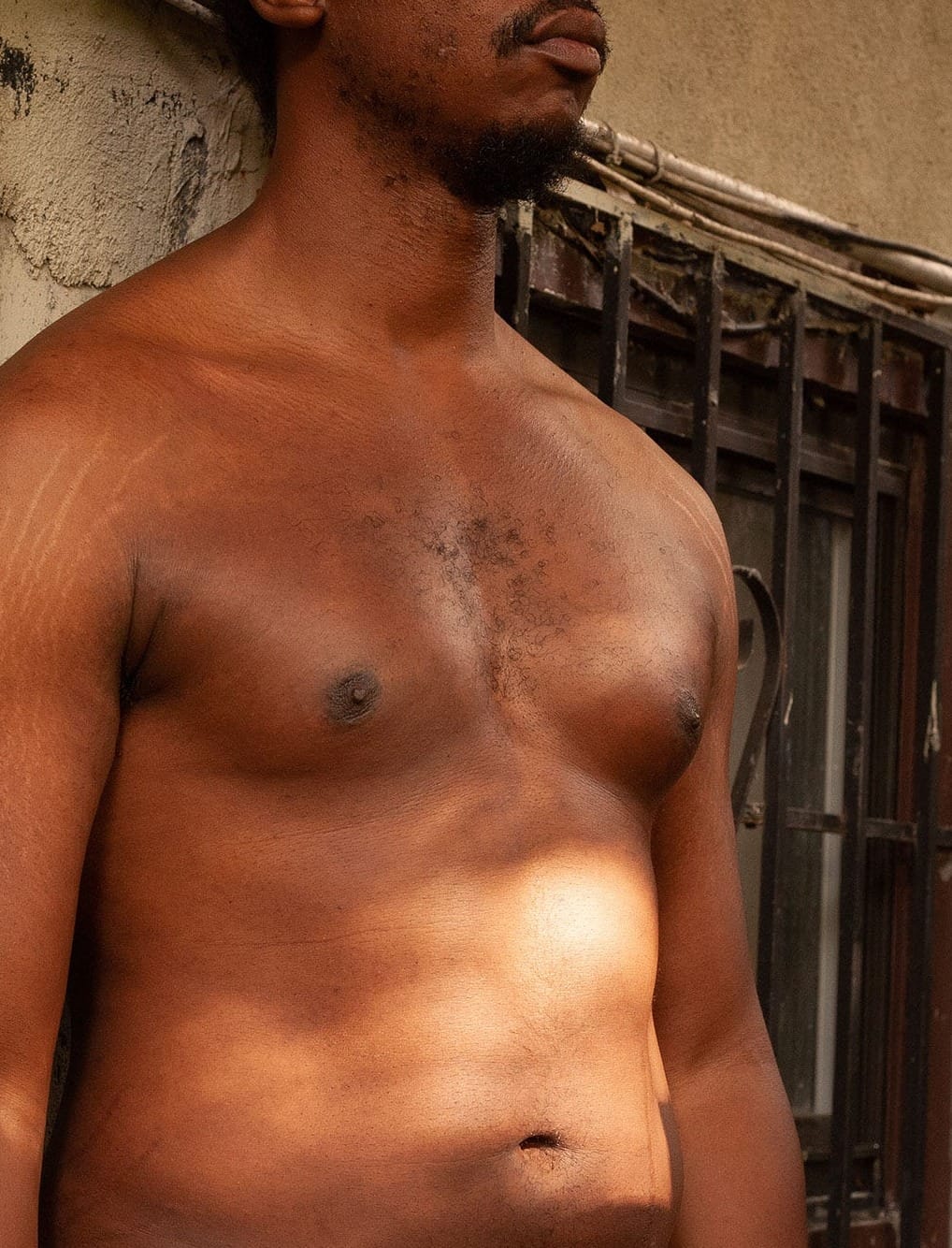

I start with a recommended “Move” goal of 720 calories. In March, I am at 990 calories and say ‘Fuck it’ on the way to 1,000. I will maintain this 1000-calorie goal even as I stop tracking meals (which are telling me how much of that 1,000 I’m burning to start the day) until about August. November to August. I am seeing myself after showers and noticing how much automation is making a difference in my muscle tone. The deep-V cut in my obliques that I’ve scrolled thousands of Pinterest thumbnails for tips on how to achieve is now vaguely present. The fitness models look like robots, and I’m not that, but I enjoy the progress photos. The knowledge that I could be on the way to a different body is both a secret shame and a source of pride. Here’s the first picture that I’m comfortable sharing with others. Content warning: a nude, middle-aged Black man will appear on your screen if you scroll down. Nude, middle-aged Black men are the not-safe-for-work signal bell.

Lesson 5: Pretend you’re always like this.

I decide to accept lovers’ compliments when the body dysmorphia is too much. I’m dating an artist named Cassandra. She has a crazy sense of discipline and a taut body. She runs to Central Park from the apartment she’s renting in Washington Heights and then to Midtown. I have never had the love of someone so fit, and I’m intimidated. She repeats ‘you’re hot’ in the way a white girl would say that. “Jesus, did you get even hotter since the last time I saw you?” At this point in February, it’s been 5 weeks of closing my rings, doing a focused calisthenics program, and eating mostly protein and leafy vegetables. I am not drinking, and she’s sober, so that helps. I feel no pressure to break that commitment. I feel impossible pressure to keep the body she thinks is hot. With the married musician, I lavish in her compliments. “Do you know how sexy you are? Like, I’m not exaggerating; you’re truly hot.” Her husband spends long stretches working on development projects out West. She cheats on him with me. She has about five years on me but is the kind of person who was always and will always be fit. The little roundness on her body gets shredded after a week of abstinence from cigarettes, running, and wine. I love her and feel lots of pressure to be sexy like the rock star white boys that I see in all her photos with her and her husband. They are wiry, druggy, and bearded. I walk in a thicker frame, nearly hairless, and with none of that style. For another lover, the nude beach is our rendezvous spot, so I make sure I crush eight sets of 10 push-ups before the two-hour commute to the Jersey shore. I am not as fit as her husband, who is young and naturally brawny with big hands and shoulders. But she’s always admiring my body, paying it compliments that, to me, a neurotic, seem fabricated. “You look so nice today, Drew. I can tell you’ve been working out.”

I have been working out; right before this.

When I stand next to her, the woman with the defined back, presidential arms, sloped shoulder muscles, and pumped thighs, I know I’m an irritably mortal man imitating an ephemeral Goddess. I want to grab at any piece of divinity I can find. Instead, I use the vision of her frame as fuel when the sweat burns my eyes and the headaches cascade in.

Lesson 6: Hydrate, (drink coffee), then hydrate again.

About 8 months into the plan, I’m getting headaches that I label “Covid headaches” because of how intense they seem and unrelated to the quarts of water I’m guzzling each day. My workouts have become a prelude to burnout in general, so I switch them up. Instead of grueling mid-winter HIIT sessions, I’m now on the basketball court, in 98-degree heat, trying to hit 15 shots around the three-point arc in about 12 minutes. This takes a month of constant shooting and reloading and shooting. Mach-Hommy’s “Pray for Haiti” pumps through my earbuds, and I’m starting to understand that, like my Beyonce moment with “Blow,” there’s a rhythm I achieve by song 6, “Marie.” My body doesn’t look the same, and I feel stronger and look leaner but notice the details. My chest seems to sag, and maybe my heart starts racing sooner than it would without the daily iced coffee. I’m no longer taking progress pictures because of a misunderstanding with the photographer I haven’t yet resolved in my mind. I am also drinking wine, drinking tequila some nights (meaning: some weeks), and generally hating the process of examining my body, and looking for ways to improve it.

Lesson 7: Hire then fire a photographer.

I love the photographer I work with. She reassured me that she will capture my body in good faith and according to what I wanted for the project. They must go viral, after all. The first round of photos she returns to me is absolutely deflating. I am a shriveling next-day birthday balloon. She’s done nothing but follow my exact instructions. In our texts, I have laid out a mood board and some themes, using the words “candid” and “mortal,” not quite sure how that will read to a photographer but also hopelessly unaware of how awful I’ll feel when I finally see my mortal self. At one point, after reviewing my notes and talking about this piece, she says, “It’s really interesting, dude, and like, a study on aging in this way I wasn’t sure it would be.”

I am a study on aging.

She meant it in the best possible way, and we have some romantic history that complicates my view of how she sees me. I shouldn’t have let that deter me, but it did, and I noticed my workouts go from daily to 5-times-weekly, then 3, and then none. In June, I assess the “Before and After” of it all and decide this project isn’t for me, nor are the photos. They will appear in this piece not because work went into them but because they’re evidence of how self-hatred can turn even beautiful photo portraits into a single, irretrievable cause for self-harm. My complaints to the photographer range from passive-aggressive (“Maybe my instruction about how the photos should look weren’t clear enough but…”) to nitpicky (“…are we sure we don’t want all the photos to be 1080 by 1920 pixels) to regretful (“It’s my fault because I didn’t know what I wanted this piece to be”). All were true; none had to do with her work.

Lesson 8: Repeat depression and regain the weight.

I don’t know when exactly I burned out, but I let others know as it was happening. Around mid-August, I started eating late at night, mashing down as many soft foods as I could find in the fridge and pantry. Slices of bread, jellies, cheeses, muffins, cookies, rolls. On Instagram, there was a record of my minor weight-loss journey’s progress, and I felt, internally, like that was enough. Nothing I did would be as compelling as the “Alone” winners risking their organs or the “Biggest Losers” vaunting cylinders of human bodies’ worth of weight in shed fat. I could not live up to the process it took to maintain a fit body, and I hated the fit body. I hate my body so regularly that I haven’t found a fitness-based answer to loving and accepting it. I can only see its remaining fat, the paunch—now hardened with bloating—the sag creeping in. I see the shadows of what I cannot fix and start resenting the need to reform in the first place. The mantra I often use, “I love my body; it is the only one I have,” feels like a jail sentence, not a freedom cry. I want to have another body that packs on muscle, that terminates fat like the cyborg-like regimen it takes to get my optimally-trained self in place.

Lesson 9: Accept the fat and the ugly.

I am Black, fat, and ugly. Those are the three adjectives I’ve most associated with my appearance, and they cut to the heart of how the body image and fitness norms tend to undermine my ability to exist. When you’re Black, fat, and ugly, you do not get to feel pain, express joy, or occupy innocence. When you’re Black, fat, and ugly, you are better off shrinking, dissipating into thin air. Your form will never be good enough. Your skin will never feel clean. But with that comes liberty I didn’t know I wanted but that I accept and rejoice in. I am so Black, fat, and ugly that your reaction, as the reader, will be to rebuke me for saying it. Instead of questioning how or why the world has given me this message, you’ll put the onus on me to unburden myself of it, to sweat it out in the gym, on the courts, in the weight room. Instead of interrogating the Whiteness that deems me ugly, that snuffs out my colors and words for its own, you will ask me to force myself inside of its picture. This is the “Before” photo of my Blackest, fattest, and ugliest. I nearly fell out when I saw how much space I took up. I couldn’t stand taking up so much space with so much Blackness. It ought to be a crime.

But it’s not. I lived through a year of being my Blackest, fattest, and ugliest, and my fittest, strongest, and most flexible. And none of it changed who I was compositionally. I had no fewer lovers, no fewer worries. I got hired and fired twice. I fell and broke down every single day, whether it was on a mattress of cheeseburgers or a hammock of asphalt. The way gravity resisted me, the way the world rejected me, the way my family loved me, and my friends supported me were not shaped by how I’m shaped. That brings me to a difficult conundrum. How do I embrace what I am in a world that is out to kill me? It’s the ultimate question of Blackness in this version of humanity, and I have not once solved for ‘x.’

Lesson 10: Know that this never ends.

It’s one year after I set out to write this. I listened to a Kiese Laymon and Tressie McMillan Cottom conversation on the Ezra Klein podcast. Laymon talked about revision, as he is apt to do, noting that revision is a privilege we’re sometimes not afforded in writing. But the great ones revise and understand that work is never complete. My self-improvement and self-acceptance project is ongoing. I may not reach some point of true acceptance, a Judeo-Christian mountaintop, a Buddhist sea of calm. I will live as Black, fat, and ugly, Black, lumpy, and beautiful, Black, plain, and soggy, and every variation of me that can step up and live. I’m thankful for that.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Andrew Ricketts' work on Medium.