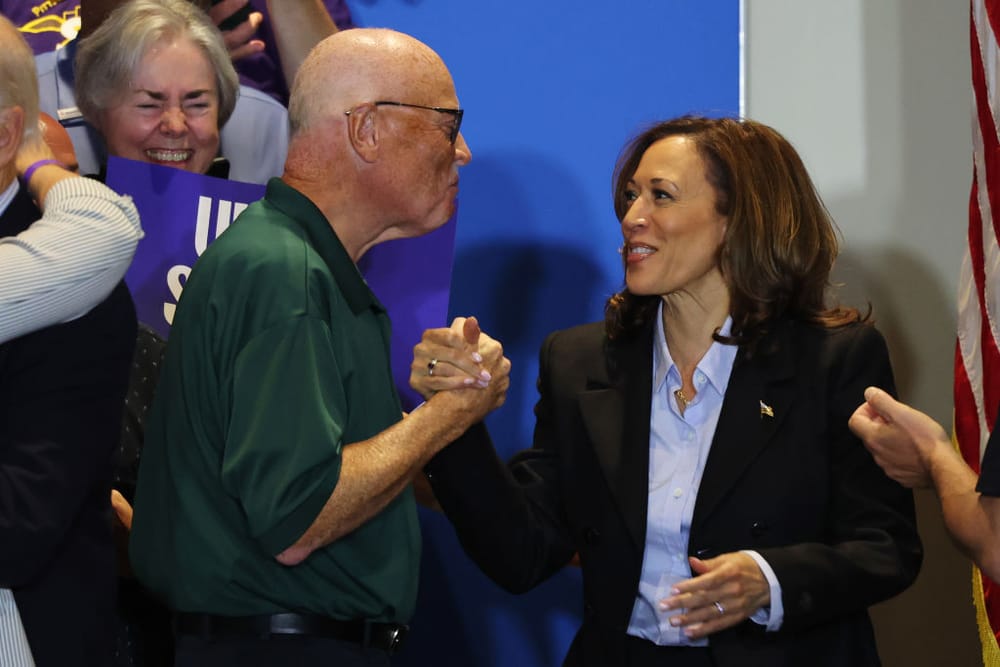

This campaign season has revealed a wide cultural gap between Black and white Americans. For instance, some have expressed utter confusion after watching videos of Vice President Kamala Harris seemingly changing her communication style for different audiences. When speaking to a crowd about the contribution of labor unions in Detroit, Michigan, she said, “you betta thank a union member for the five-day work week and sick leave.” However, when speaking to a crowd in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, she said, “thank unions for sick leave” and “thank unions for family leave.” Of course, she carried the same message to both groups: union workers have successfully advocated for better quality working conditions for Americans. Yet, some decided to focus on the differences in her speech patterns. Despite codeswitching being a common practice within the black community, some conservatives claimed that this linguistic shift was evidence of inauthenticity, essentially questioning Harris’ blackness. Their confusion highlights the need for more constructive conversations on race and communication.

Perhaps, if American students were allowed to learn about race in school, they could take a lesson on codeswitching. Of course, to understand the practice, they’d have to know about the chattel slavery system, which stripped enslaved Africans of their original languages and cultural practices. And about the way anti-literacy laws prevented Black people from reading, writing, and communicating using the written word. Then, they’d learn that African American Vernacular English (AAVE), colloquially referred to as Ebonics, is a valid form of communication recognized by sociolinguists, not broken English, as some assume. “Bogus,” for instance, derives from the Hausa, a West African language, and means “fake” or “fraud.” Likewise, there are unique sounds associated with the variant, like reducing the pronunciation of some consonants in words like “that” to “dat,” and grammatical rules, like omitting the verb “be” from sentences because this device is seen as superfluous. However, since black history is inadequately taught, most Americans are not formally introduced to AAVE and look down upon Black people whose expressions deviate from standardized English. Despite the linguistic complexity and depth of the variant, many white people make racist assumptions about Black people who embrace this dialect.

Kurinec found that speech can activate racial stereotype endorsement, triggering expectations that contribute to bias in eyewitness description and identification. When George Zimmerman stood trial for fatally shooting a 17-year-old Black teenager, Trayvon Martin, in 2013, the jury heard from a variety of witnesses. Perhaps the most memorable was Rachel Jeantel, Martin’s friend, whom he spoke with on his way home. She overheard much of the conflict. However, some responded to Jeantel’s testimony by mocking her because she was a dark-skinned woman who expressed herself using AAVE rather than standard English. She was chastised because she couldn’t speak “the Queen’s English,” and her testimony was publicly doubted. This linguistic prejudice may have contributed to the jury’s decision to acquit Zimmerman. Rachel Jeantel’s experience has been widely cited as an example of linguistic discrimination. She was called “inarticulate,” “thuggish,” and even “hostile” simply for sharing her story.

Given the discrimination Black people experience when they speak freely, it makes sense why many adapt their manner of communication to fit their audience. Nevertheless, we should also acknowledge that not every Black person codeswitches, as some have limited experience communicating with white people and were never socially pressured to learn this survival skill. What many Americans consider “professional” communication is inundated with white-centered standards masked as neutral, which is why Black people should never be pressured into codeswitching. As we’ve seen with the mistreatment of Rachel Jeantel, this expectation is exceedingly harmful, as it essentially dehumanizes anyone who deviates from speaking standardized English.

In terms of Kamala Harris’ communication in question, it’s unclear whether the Vice President intentionally switched her use of language. For most Black people, code-switching is reflexive, not a pre-meditated behavior. And yet, the confusion surrounding her use of language exposes a racial cultural gap. Since the topic of race and racism or even the black experience in America, is shunned in the classroom, most never formally learn about the topic of codeswitching. Of course, some will argue that white people don’t need to know about codeswitching, that it’s on a need-to-know basis. However, when white pundits and journalists routinely misunderstand Black political candidates like Harris, it’s clear that at least some need to understand the concept.

For instance, Peter Dosey, a White House correspondent for Fox News, asked White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre, “since when does the Vice President have what sounds like a Southern accent?” referring to the viral video showing her using slightly different verbiage in Pittsburg than Detroit to talk about unions. However, it was clear that “southern” was referring to “Black.” After all, Black people in New Orleans, New York, and Los Angeles say “betta,” it’s not like this language is exclusive to the South. Once again, the lack of formal education about the Black experience and the practice of code-switching facilitates confusion. Others would consider this a case of weaponized incompetence.

Black people are not the only group that code-switches. Language is contextual. If an adult changes the inclination of their voice and vocabulary when they speak to a group of children, they’re codeswitching. If a man puts some extra bass in his voice when he talks to a woman he’s attracted to, he’s codeswitching. And the same goes for wealthy people changing their lingo when speaking to working-class folks or white people speaking to Black people. The reasons for codeswitching vary because language is contextual. Thus, it makes sense that Black people living in a white-centered society engage in code-switching. It’s a strategy to mitigate the cruel stereotypical assumptions about their intelligence, experiences, and leadership capacity. From former president Donald Trump asking weeks ago when Harris “became Black” to pundits claiming her codeswitching is evidence the Vice President isn’t really Black, despite having a Black father, the American public’s ignorance on the topic of race is being politically exploited.

Codeswitching is not a new practice, as it is a practice rooted in chattel slavery when Black people were expected to abandon their African languages and only speak English, French, or Spanish, the languages of their enslavers. It should shock no one that these social conditions produced dialects that stray from standardized forms. Furthermore, it is common for leaders to shift their communication style to meet the needs of their organization. Adaptive leadership, for instance, allows managers to switch gears and make “transitions in dynamic contexts. Consequently, a leader who can code-switch may be more effective than those who cannot. Once again, Black Americans’ communication skills are often undervalued and seen as a detriment when it could be an advantage if racism didn’t blur the country’s collective lens.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Allison Gaines' work on Medium.