It should not be lost on anyone, and certainly not the long-term fans and historians of pop music, that before there is a song, there needs to be a songwriter. Singers need songs, and no one understood that better than the late legendary song stylist Jerry Butler, when he created the Jerry Butler Songwriters Workshop in Chicago in the early 1970s. Butler’s workshop had an impact on soul music throughout the 1970s eventually figuring in the rise of Natalie Cole as the first real challenge to Aretha Franklin’s status as the “Queen of Soul".

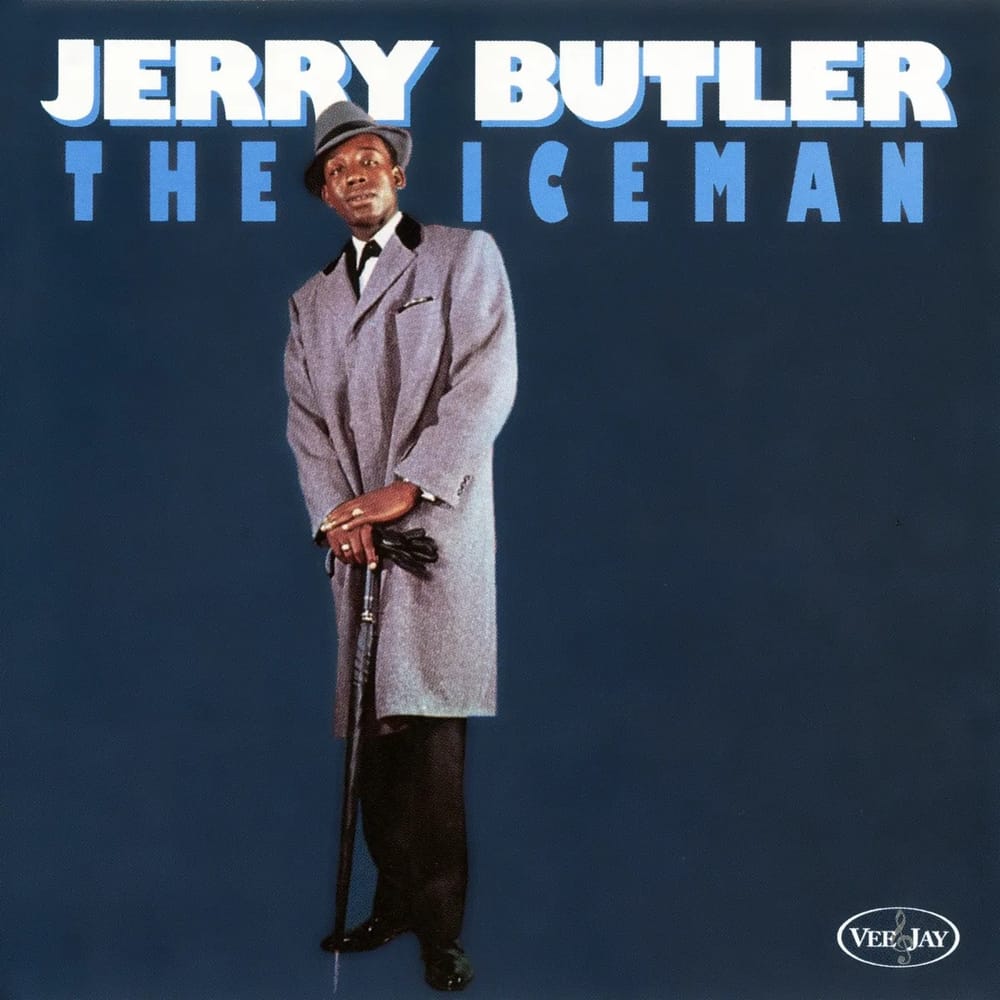

Jerry Butler aka “The Iceman” (for his cool, Sagittarian demeanor) began his professional singing career in the late 1950s as the initial lead singer for The Impressions. Butler was 18 years old when the Chicago based group topped the pop charts with “For Your Precious Love” in 1958. Among those in the group was a 16-year-old songwriter and guitarist by the name of Curtis Mayfield, later to become one of the most recognizable singer-songwriters of his generation.

Though Butler was a member of The Impression for only a short time, he forged a productive professional relationship with Mayfield that led to Butler’s success recording as a solo artist in the early 1960s. The Butler/Mayfield collaboration led to early hits like “Need to Belong” and “He Will Break Your Heart,” recorded for the Black-owned Chicago-based Vee-Jay Records, whose roster included Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons. Vee-Jay also distributed the early US releases of The Beatles.

Butler also had access to the remnants of Tin Pan Alley — the cadre of New York based songwriters and producers that were at the heart of American popular music in the early 20th century. In Butler case, he scored hits with Brill Building residents like Hal David and Burt Bacharach (“Make It Easy On Yourself”).

When Butler signed with Mercury Records in 1966 and was again in need of strong material, he turned to two young and unproven songwriters and producers from Philadelphia. Butler’s work with Leon Huff and Kenny Gamble coincides with the most productive and popular period of the soul singer’s career with hits like the ballad “Never Gonna Give You Up” (later covered by Isaac Hayes on Black Moses), “Hey Western Union Man” and “Only the Strong Survive,” which became Butler’s first Gold single. Gamble and Huff’s work with Butler gave an early inkling of the uplift music that Gamble and Huff would become known for in the 1970s with their Mighty Three Publishing company (with Thom Bell) and Philadelphia International Records.

Recalling his work with Gamble and Huff, which produced the legendary The Ice Man Cometh recording, Butler writes in his autobiography Only the Strong Survive: Memoirs of a Soul Survivor, “Huff would be on the piano , while Kenny and I would come up with lyrics. Huff and Kenny would come up with concepts and play some chords, and I started singing. That’s how we came up with ‘Never Gonna Give You Up’.” When Mercury Records balked at Gamble and Huff’s efforts to earn a greater percentage of the profits from their production efforts with Butler, the relationship was dissolved in late 1969. Butler, though, later recorded two albums with the duo for Philadelphia International Records a decade later.

No longer able to work with songwriters and producers of the caliber of Gamble and Huff, and Curtis Mayfield — folk who literally defined the sound of soul music for more than a decade — Butler found himself at a professional crossroads. Butler writes in Only the Strong Survive,

“I was in a terrible dilemma. Should I risk my professional reputation recording substandard material? Or should I use what I had learned over the years to lay the groundwork for developing songwriters who would supply me — and others — with quality songs for a lifetime. I chose the latter.”

The Jerry Butler Songwriters Workshop was founded in Chicago in January of 1970. The following year, the workshop became a joint venture with the Chappell music publishing company which made an initial investment of $55,000 for the project. The Jerry Butler Songwriters Workshop did little to revive Butler’s career — though his second Gold single “Ain’t Understanding Mellow” with Brenda Lee Eager was a product of the workshop. By 1972 though, the workshop had generated $4 million in records sales and produced about 30 chart singles recorded by the likes of The Dells, Isaac Hayes, Aretha Franklin, Oscar Brown, Jr. and Betty Everett.

Despite its modest success, the real story of the Jerry Butler Songwriter’s Workshop wasn’t what it produced, but the talent that came through its doors, and went on to greater success. Workshop veterans include Terry Callier, who with fellow workshop participant Larry Wade, worked on The Dells’ Freedom Means (1972) recording which produced their classic “The Love We Had (Stays on My Mind)”. The duo also worked on Callier’s own brilliant Cadet recordings Occasional Rain (1972) and What Color is Love? (1973) — both produced by Charles Stepney, architect of the classic Earth, Wind and Fire sound. Other veterans of the workshop were Len Ron Hanks and Zane Grey who co-wrote L.T.D.’s breakthrough hit “(Every Time I Turn Around) Back in Love Again”(1977) and later scored their own Disco hit “Dancin’” (1978) recording as Grey and Hanks.

The most successful veterans of The Jerry Butler Songwriters Workshop were the duo of Chuck Jackson and Marvin Yancy. Jackson, (not be mistaken for the hit-maker from the 1960s), was the brother of the Reverend Jesse Jackson, and an art director at Playboy Magazine when he joined Butler’s workshop. Yancy was the musical director and pianist at his father’s Chicago Church when he met Jackson at Reverend Jackson’s Black Expo in 1971. Jackson and Yancy made a musical connection.

The initial fruits of Jackson and Yancy’s efforts was the formation of the group The Independents which featured Jackson, Yancy (who preferred staying in the background) Helen Curry, Maurice Jackson (no relation), and later Eric Thomas, who was a member of Reverend Jackson’s Operation PUSH Choir. Recording with dual leads Curry and Chuck Jackson, in the spirit of the deep soul recordings of the Soul Children, The Independents produced a series of moody and gospel inflected mid-tempo and ballad numbers including “Leaving Me,” which sold over a million copies in 1973, “Baby I Been Missing You,” “The First Time We Met,” “In the Valley of My World” (later sampled on Jay Z’s remix of “Allure”) and the stirring “Let This Be a Lesson to You.”

Despite the group’s moderate success, Jackson and Yancy disbanded The Independents to seek other opportunities. Jackson and Yancy’s fortunes changed when they had a chance encounter with the daughter of Nat King Cole, who was performing at a local club in Chicago. Natalie Cole had been performing a collection of pop standards and soft rock songs, contemplating signing with a major label, but wary of being “exploited” as the daughter of a pop icon. That all changed when Jackson and Yancy took Cole into Curtis Mayfield’s Chicago studio and recorded the demo for what became “Inseparable.”

As Cole told The New York Times’ Stephen Holden in 1976, “I went back to R&B with my producers who gave it a little extra sophistication.” That sophistication translated into Cole’s first album Inseparable (1975), recorded for her father’s longtime label Capitol. The album eventually spawned two chart-topping singles — the title track and “This Will Be” — and earned Cole two Grammy Awards in 1975 including the award for “Best R&B Performance, Female” — the first person not named Aretha Franklin to win that category in 8 years.

With musical taste changing, Jackson and Yancy (who was briefly married to Cole in the late 1970s) packaged Cole with a pop-jazz sound, not unlike that of Cole’s father and Jerry Butler in the early 1960s, but with a Gospel flair. The Cole, Yancy, Jackson collaboration produced five albums and several million-selling singles including 1977’s “I’ve Got Love on My Mind” (from Thankful) and “Our Love” which was released later in the year on Unpredictable.

No doubt Jackson and Yancy’s time at The Jerry Butler Songwriters Workshop, contributed to them becoming better songwriters, but also helped them become much more adept at managing talent in the studio — something that is increasingly a lost art.

For Butler’s part, he was always clear about his investment in the songwriter’s workshop. As he told Rolling Stone magazine in 1973, “The idea for the workshop came out of self-interest. I had obligations to do thirty sides for Mercury…Tin Pan Alley, where you used to be able to go get a couple of songs, has died for all intents and purposes.”

Butler added, “I knew Chicago was not the music center that it once was. But at the time, I knew there were a number of young cats in Chicago with a lot of songwriting talent, who just didn’t have any place to take it to. And even more importantly, nobody to encourage them. (quoted in Robert Pruter’s Chicago Soul).”

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.