“I hear voices, I see people…talking ‘bout everything is everything” and though the lyrics aren’t from the late Maurice White, co-written instead by fellow Chess Records alum Phillip Upchurch, and first recorded by the late Donny Hathaway, this line from Earth, Wind & Fire’s second album The Need of Love (1971) says everything about the music of Earth, Wind and Fire and its longtime conjuror.

“Everything is Everything” is from the fledgling Earth, Wind and Fire’s time with Warner Brothers. The music, which shared wide open spaces with that of early Funkadelic, the Isley Brothers of the early T-Neck era (both before and after the 3+3 formation), and the trio incarnation of LaBelle, could only be called experimental if you didn’t know the archive that they all were drawing from. The music was dripping with the radical possibilities of the abstract as a means of futuring Blackness, cause as Margo Crawford might say, what else was the Black Arts Movement about?

Yet the bohemian funk that grounded those first two Earth, Wind and Fire albums — an index of musical Blackness in transition — White jettisoned, choosing instead a new label, and a new brand (perhaps), under the helm (for a very short time) of an industry Godfather, who was developing a certain talent for transitioning the Bold the Black and the Brown, into usable commodity. In Earth, Wind & Fire, Clive Davis, perhaps had the inroads to the Black radio audiences he sought, something never intended for say Miles Davis and Carlos Santana and lost with the demise of that classic Sly & the Family Stone sound.

No doubt Clive Davis was hedging his bets with the unproven Earth Wind and Fire; as he was buying out the group’s contract for CBS, he was also plotting to provide seed money to an entity coming out of Philadelphia that would establish itself as the definitive Black music brand of the 1970s. Davis was no longer at CBS records when the music of Earth, Wind and Fire and Philadelphia International Records (The O’Jays + Harold Melvin & The Bluenotes + Teddy Pendergrass + Lou Rawls) became the Sound of the 1970s; it bears reminding though that well before Davis revitalized the career of Aretha Franklin and shepherded the career of Whitney Houston, that one of his first signings at Arista Records was Gil Scott-Heron.

For White, the decision to move to Columbia and the possibility of mass appeal, may have had a lot to do with his time growing up in South Memphis and playing drums in the Ramsey Lewis Trio. As Jazz titans debated the merits of keeping the hard bop, boppable, or freeing it to fly, Ramsey Lewis kept it in the pocket and toe-tapping accessible, and you couldn’t say after hearing “The In Crowd” for the 77th time, that his band didn’t have chops. Hell even Lewis’s sidemen — Drummer Isaac “Red” Holt and bassist Eldee Young, — ruled a summer with the instrumental “Soulful Strut” (1969).

Listen to any of those first Earth, Wind & Fire albums for CBS, including Last Days and Time (1972), Keep Your Head to the Sky (1973) and their commercial breakthrough Open Our Eyes (1974), and what is clear is that White and Earth, Wind and Fire had something to say — about spirituality, community, love, AfroFuture continuums — and to White’s credit, he wanted to reach the widest audience possible.

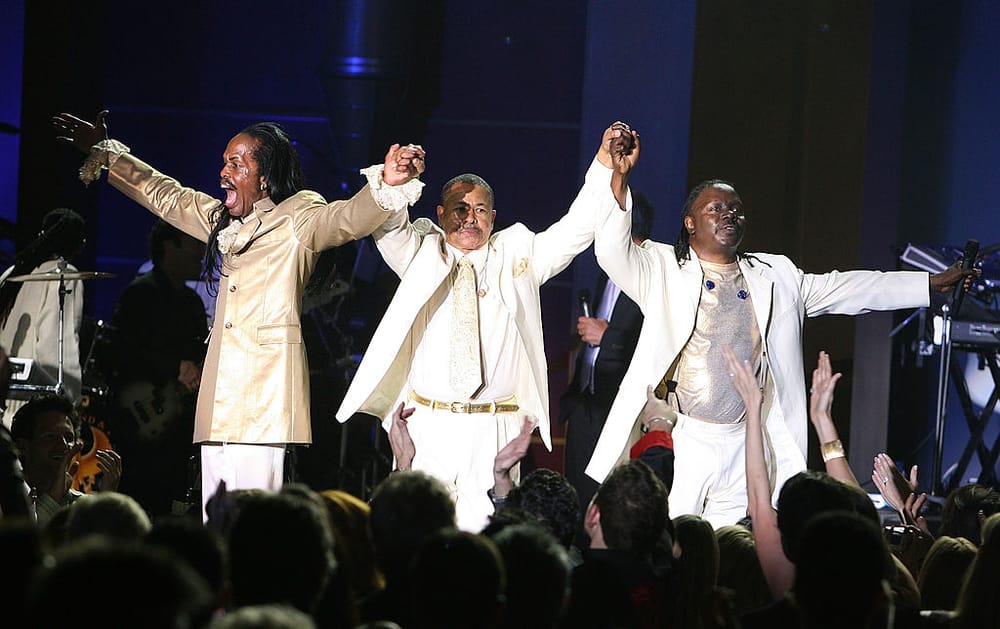

Songs like “That’s the Way of the World,” “September,” “Sing a Song,” “Shining Star,” “After the Love is Gone,” and “Boogie Wonderland” are as quintessentially 1970s Pop as anything produced by Chicago, The Eagles and Elton John — more accessible than most of David Bowie’s or Fleetwood Mac’s catalogue from that period.

Yet the sustainability of Earth, Wind and Fire was the duality of a group that back-channeled Black uplift for audiences bereft of Black decoder rings, while making sure that the band remained committed to Album Oriented Soul, cause folks needed more than the hits to survive — and needed to have a little something to claim for themselves.

Show me a Black-Over-Age-50 Earth, Wind and Fire fan, and they riffing about “Devotion,” “Keep Your Head to the Sky,” “Fantasy” — from arguably the band’s most complete album statement All n’ All — “Wanna Be with You,” “Side by Side” or the collaboration with Ramsey Lewis on “Sun Goddess,” which gave the late pianist his biggest hit since “The In Crowd.”

And not leaving anything to chance, Earth, Wind & Fire always had a little something for when the Blue Light came on. Everybody will cite “Reasons” — especially the live version from Gratitude where vocalist Philip Bailey and late saxophonist Don Myrick engage in a form of call-and-response that competes with the best we’ve heard on any Sunday morning — but there are so many others: “Can’t Hide Love,” “Lover’s Holiday,” “All About Love,” and a personal favorite “Be Ever Wonderful.”

True that Earth, Wind & Fire’s ability to craft pop hits, along-side B-side album grooves and timeless drags was matched by them Philly boys, Gamble and Huff, but where Philadelphia International needed a cast of many, including lesser knowns like Bunny Sigler, Dee Sharp Gamble, The Three Degrees, MFSB (PIR’s backing band), and The Jones Girls to articulate their musical vision, Earth, Wind & Fire matched that productivity in one self-contained band, and of course the Phenix Horns (led my Myrick).

White, though, could also claim his impact on artists like The Emotions, whose breakthrough release Rejoice (1977), with the still timeless “Best of My Love” (written with EWF’s Al McKay), was produced by White, as well as Deniece Williams’ debut This is Niecy (1976), which includes the classic “Free” and the brilliant “If You Don’t Believe.” White also produced Jennifer Holiday’s debut Feel My Soul (1983), three Ramsey Lewis albums, and much later in his career, two albums for the Jazz supergroup, Urban Knights (with Grover Washington, Omar Hakim, and others).

In the mid-1980s, as Earth, Wind and Fire took a four year hiatus, White released his eponymously titled solo album, led by a cover of Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me” and the gentle-stepper “I Need You.” In that era, he also contributed production to 1970s pop-chart peers Neil Diamond and Barbra Streisand.

Earth, Wind and Fire, and Maurice White in particular, will likely never get deserved recognition for its success during the band’s heyday of 1974–1982, and perhaps that is as it should be. The Phoenix rises again, and importantly, the right folk will recognize it when they see…and hear it.

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Mark Anthony Neal's work on Medium.