It was a Sunday in the spring of 1973. Like most every other Sunday that year, I was at Zion Baptist Church in Minneapolis, MN. A traditional part of the service was welcoming our guests. That day, a man stood up and introduced himself, “I’m George Foreman, the Heavyweight Champion of the World.”

There was a brief murmur, especially among the youth who typically sat in the rear of the church. Foreman spoke from where he was standing in one of the front rows. He thanked Pastor Curtis Herron for having him and gave God the glory for his success. When service ended, he greeted members in the foyer in front of the church.

It wasn’t announced he would be there. About half of those attending the service exited through a rear exit toward the parking on that level and missed their opportunity to meet the champ. I was one of those leaving from the front and got in line to shake his hand. I was sizing him up while awaiting my chance.

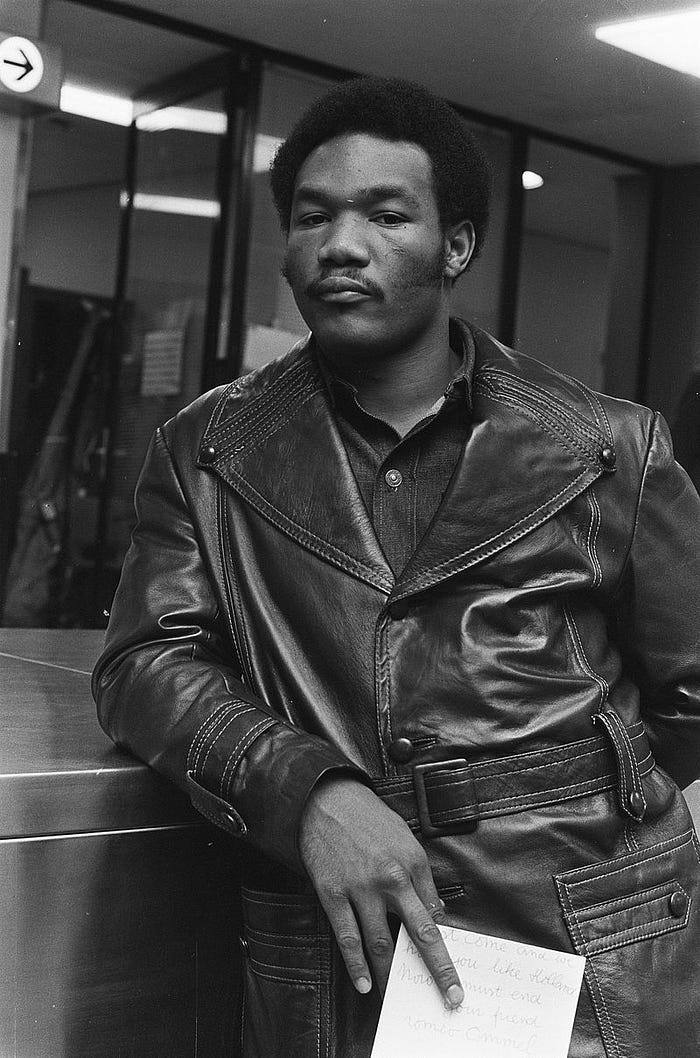

I was a senior in high school, and at 6'6", I was the center of my basketball team. I was two inches taller than Foreman; he outweighed me by about 15 pounds. I’d previously met professional athletes with the Minnesota Twins and Minnesota Vikings but had never seen a more physically imposing figure than George Foreman. He had a barrel chest, and even in a suit, reeked of power. I’d followed Foreman since his Gold Medal performance at the 1968 Summer Olympics. He won his first 37 professional fights before demolishing Joe Frazier in two rounds to become the World Champion. Foreman knocked Frazier down six times in six minutes. A few months later, he was right in front of me at my church.

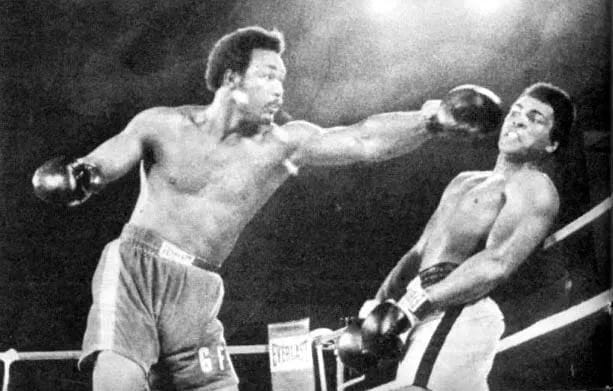

While Foreman certainly was the champ, I wasn’t sure he’d learned how to be the world champion outside of the ring yet. He seemed a bit shy and insecure. I was quiet, but he was even more so. He wasn’t the genial gentleman you now associate with the George Foreman grill. He looked as hard as the streets where he was raised in Houston. There was no reason to believe this man could ever lose a professional fight until he did a year and a half later when he fought Muhammad Ali in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Zaire, Africa.

Meeting George Foreman made an impression on me as a seventeen-year-old, but he wasn’t my boxing hero. That was Cassius Clay, who had been stripped of his crown for refusing induction into the US Army to fight in the Vietnam War. Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964 after converting to the Muslim religion. Ali had his crown taken away on April 28, 1968, when he was in his boxing prime. For over three years, Ali was prevented from boxing for his religious convictions. He finally got two fights, one he won against Jerry Quarry in Georgia, where there was no boxing commission to prevent it. He lost in an attempt to regain the title from Joe Frazier, who had become champion during Ali’s absence from the ring. Not before winning his most important fight, with the Supreme Court deciding 8–0 for Ali’s right to sit out the war as a conscientious objector.

“I ain’t got no quarrel with them, Viet Cong,” Ali famously said.

The majority of Ali’s early fights weren’t televised. There were snippets from the 1960 Olympics, culminating with a Gold Medal. Nobody believed the 18-year-old would win but himself. While Foreman was respected for his prowess, Ali was revered, mainly because he talked the talk while walking the walk. People tuned in on the radio during an Ali fight, and the nation came to a halt. Foreman ran around the ring waving a tiny American flag when he won Gold. Ali returned home and saw the promises America wasn’t living up to. Ali later threw his Gold Medal into a river. He chose a different path and a different religion.

Defeating George Foreman gave Muhammad Ali back the Heavyweight Title. He knew how to be the champ, exuding confidence in any environment. I met Ali in 1975 when he came to Fisk University. I didn’t hear him speak in The Appleton Room in Jubilee Hall, but I was part of the antics afterward.

Word spread of Ali’s presence on campus, and when he left Jubilee Hall, hundreds of students gathered and followed him. He stopped in front of one of the cafeteria entrances and started picking out the tallest and most athletic-looking young men to gather around him in a circle; I was included among them. He struck up a fighting pose as if challenging us all to a fight. He’d throw a jab and turn to face the next man, none of us attempting to close the distance between us.

Ali wasn’t as imposing as George Foreman had been two years earlier. While certainly louder, he also seemed softer and less threatening. While being in the ring with George Foreman was too scary to contemplate, I looked at Ali and thought he might be beatable. I had bulked up a little from high school and had a good three inches on him with comparable reach. Any thoughts of beating Ali evaporated when he flicked that left jab in my direction. After the fact, I felt the gust of air that originated an inch from my chin as he withdrew his fist. It took a few seconds to register what happened because I had never seen him throw the punch.

They say you should never meet your idols, and some things I saw that day were troubling. Ali was still married to his second wife, Khalilah, at the time. His mistress and future third wife, Veronica Porsche, was sitting in a nearby limo while he flirted with several Fisk co-eds. I wavered between jealousy and judgment; no one confronted Ali that day about his womanizing.

I’m not sure who the current Heavyweight champion is today. There are four designated bodies, two of which, the WBO and WBA, have more than one champion. I recognize the name Tyson Fury, the WBC champ, though I could pass him on the street and not recognize him. There was a time when the Heavyweight Champion of the World was more recognizable than Tiger Woods in his prime. I met two of them at the height of their careers, and they made quite an impression.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of William Spivey's work on Medium. And if you dig his words, buy the man a coffee.