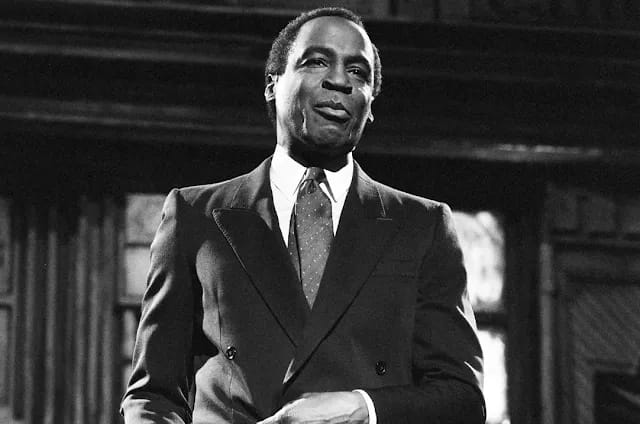

There's a line in 1989's Lean On Me, a biopic of New Jersey educator Joe “bat man” Clark, that soars above the rest. Ostensibly a star turn for Morgan Freeman — released shortly before his breakthrough in Driving Miss Daisy — it was Robert Guillaume, as Freeman’s supervisor, who stole the scene when he quiped “I’m the head nigger in charge.” Guillaume, with his deadpan comedic delivery, made his name stealing such scenes as “Benson DuBois” — the role he is most remembered for — in the sitcoms Soap (1977–1979) and Benson (1979–1986).

Though Guillaume’s name evokes origins in some far off French Caribbean island, he was born Robert Williams on November 30, 1927, and by his own definition was “a bastard, a Catholic, the son of a prostitute, and a product of the poorest slums of St. Louis.” (Guillaume: A Life, 1). It was in the Catholic church, that the grandmother that raised Guillaume took him regularly, where he realized his initial talent for singing church music. Guillaume’s singing voice would serve him well on Broadway and off in the 1960s, allowed him to attend and drop out of both Saint Louis University and Washington University in St. Louis, and eventually to star in a critically acclaimed stint as the star of The Phantom of the Opera in 1990.

Guillaume was well past thirty when he finally left St. Louis in the late 1950s, leaving behind his estranged wife Marlene and their two young sons Kevin and Jacques, and headed to Cleveland to join the Karamu House theater. Founded in 1915 as The Playhouse Settlement by Oberlin graduates Russell Jelliffe and Rowena Woodham, and renamed in 1941, Karamu House is one the oldest African American Theaters in the country. Alumni of Karamu House included veteran actor Bill Cobbs (New Jack City, The Bodyguard, Night at the Museum), Vanessa Bell-Calloway (All My Children, Biker Boyz, Survivor’s Remorse), and Ron O’Neal of Superfly fame.

It was in Cleveland that Robert Williams officially became Robert Guillaume; the late actor recalled in his memoir Guillaume: A Life (with David Ritz), “Robert Williams was too common a name. Besides I knew of several Robert Williamses on death row…Frenchifying Williams into Guillaume was a classy move.” Guillaume also recalled the advice of Karamu’s stage director Benno Frank who told Black members of the troupe, “White people…may need a method to find their feelings” — a shot at the method acting techniques of the era — “You have no such problem.”

When composer and Karamu alumnus Howard A. Roberts, who created the score for Alvin Ailey’s legendary Revelations (1960), came to Cleveland to recruit talent for Free and Easy, a musical about Black jockeys in which Roberts was musical director, Guillaume was ready to go. Guillaume joined a cast that would include actress Beverly Todd (Queen Sugar’s “Mother Brown”) and famed Black hoofer Harold Nicholas.

Settling in New York City with his lover Karin Berg (a devout Catholic, Guillaume remained married to his wife Marlene for another twenty-years), Guillaume would contribute to several theatre productions in the 1960s including Kwamina (1961), Fly, Blackbird (1962), Tambourines to Glory (1963), starring future Oscar winner Lou Gossett, Jr. as lead and based on music from Langston Hughes, and Golden Boy, which starred Sammy Davis, Jr.. Guillaume remembers being somewhat intimidated by Davis — then at the peak of his powers and popularity — noting that “Sammy moved in a world that felt too fast, too extravagant, too fabulous to include me. He gave the impression of never sleeping…his partying — like his performances — took on a mythic proportion. So, I kept my distance.” (84)

Guillaume translated his new found visibility into the role of “Sportin’ Life”, in a European tour of Porgy and Bess, which also allowed him to perform alongside his vocal hero William Warfield, who starred at Porgy. The touring production also allowed Guillaume to reconnect with his sons Kevin and Jacques, who traveled with their father when Porgy and Bess settled in Israel during the summer of 1966.

Guillaume was well aware that his choice to travel abroad was an effective exile from the political happenings in the streets of America, and ironically a source of tension with his partner Karin Berg, a White woman and Freedom Rider, who was being increasingly politicized by the Civil Rights Movement. Guillaume wrote in his memoir, “I take no pride in confessing to sitting out the great social, political, and moral movement of my time…My actions were centered on myself. I wanted to survive. I wanted to make it; I wanted to work.” (81)

To his point, Guillaume was over 40-year-old when Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in April of 1968, and as the 1970s began, he watched his old Karamu running partner Ron O’Neal become a major Hollywood star on the strength of his star-turn in Superfly (1972). O’Neal’s success was a cautionary tale for Guillaume, as the former’s success betrayed his formidable talents as a classically trained actor and singer; as “Superfly” resonated in the mainstream, few producers and directors took the opportunity to cast O’Neal in serious roles. It was in the O’Neal directed sequel Superfly T.N.T., that Guillaume made his Hollywood film debut — playing a seemingly autobiographical expatriate singer in Rome.

Yet as Blaxploitation-fare like Superfly and Shaft began to wane, it was the television sitcom that began to create opportunities for Black actors and actresses. Guillaume made appearances on Julia (1968) with Diahann Carroll, Marcus Welby, MD. (1975) and All in the Family. Guillaume likely caught the attention of the latter show’s producer Norman Lear, during his turn as the star in a revival of Purlie! (based on the Ossie Davis play Purlie Victorious), in late 1972. Lear famously scouted Sherman Helmsley for the future “George Jefferson” who portrayed the character of “Gitlow” in the same production.

With the success of series like Sanford & Son, The Jeffersons, The Flip Wilson Show and Good Times — shows all driven by comic talents — Guillaume never felt that television was an option for him. Guillaume was in fact, back on Broadway, earning a Tony Award nomination in 1977 as “Nathan Detroit” in an all-Black revival of Guys and Dolls, when the opportunity to star as a butler in a new sitcom presented itself.

Ironically it was Ron O’Neal, whose own career with shrouded by charges that he undermined Black racial progress by portraying a drug-dealing pimp, who insisted that Guillaume not take a role that was “ a step backwards. Television is still operating in the dark ages of Amos & Andy.” (147). The series was Soap (1977–1981), which broke new social ground regarding issues of religion, mental health, and homosexuality — Billy Crystal portrayed mainstream television’s first homosexual character in what was his breakthrough role. Of the character of “Benson,” Guillaume wrote, “For a Black man the material was complex. The character was irreverent. The question was, how to express such irreverence? In reading the lines, I felt an immediate rapport with this butler called Benson…I saw Benson as Mantan Moreland’s revenge,” in reference to the Black comic actor who was well known for playing such roles.

Guillaume’s “Benson DuBois” was easily the wisest character on the series — that was part of the joke — but also a character with a wealth of empathy, which translated into an Emmy Award in 1979 for the actor. For Black audiences, the character’s appeal might have been that he was able to “talk back” in ways that had been denied actual Black domestic workers. As such “Benson” was an index of changing social opinions regarding race.

When Guillaume was tabbed to do a spinoff of Soap, simply called Benson, the character’s transition from head of the fictional California Governor’s household to State Budget director, to Gubernatorial candidate, mirrored the real-world politics of Los Angeles mayor Tom Bradley’s campaign for Governor of California. Bradley lost the 1982 election by 100,000 votes and was defeated a second time by then incumbent George Deukmejian, months after Benson left the airwaves. Four years later Douglas Wilder, became the first African American governor since Reconstruction, when he was elected the 66th governor of the State of Virginia. Guillaume was nominated four times for Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series, before finally winning in 1985. For nearly a decade, “Benson DuBois” was in fact, the “Head Nigger in Charge” on mainstream television.

In the 1990s, Guillaume was introduced to a new generation courtesy of his narration on the HBO children’s series Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child (1995–1999). The series, produced by Guillaume’s second wife Donna Brown Guillaume, re-told classic fairytales with multicultural references and representation. Guillaume was also famously cast as the voice of Rafiki in The Lion King. Guillaume recalled thinking that Disney wanted him to play Mufasa and complained to his agent “why…must a black man always play the monkey?” When he realized that James Earl Jones was chosen to play the king, he sheepishly told his agent, “I’ll play the monkey.”

The Lion King episode, in many ways encapsulates Guillaume’s career; overshadowed by Louis Gossett during his early years on Broadway, and by his best friend Ron O’Neal during the Blaxploitation-era, and by the likes of standup comedians like Flip Wilson, Redd Foxx and Bill Cosby on television, it might be easy to overlook Guillaume’s legacy.

Yet in a career defined by a dogged determination to breakthrough, Guillaume became a certified star at an age — 50 — when most are beginning to see diminishing opportunities. It was such determination that Guillaume put on display in one of his last and most memorable roles, as television producer Isaac Jaffe on the short-lived series Sports Night, which earned Screen Actors Guild nomination for Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Comedy Series in 2000. In a cast that featured actors Josh Charles and Peter Krause (a riff on the classic ESPN pairing of Keith Olbermann and Dan Patrick), Felicity Huffman, and Joshua Malina, Guillaume did as he always had; stole scenes. When Guillaume suffered a stroke midway through the first season — by then in his early 70s — not only did the actor return to work, but his affliction was also written into the storyline.

Robert Guillaume died at age 89 on October 24, 2017. He was survived by his wife of thirty-plus years Donna Brown Guillaume, three daughters, Patricia, Melissa and Rachel, and one son, Kevin. His son Jacques preceded him in death in 1990.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Mark Anthony Neal's work on Medium.