In far too many minds, Jackie Robinson — a legitimate national hero — is the direct antithesis of contemporary professional sports figures. Whether they are discussed on Sports radio broadcasts or hosting their own podcasts, contemporary athletes — in this era of athlete empowerment — are invariably described as selfish, money hungry, and inaccessible. While such descriptions are used to depict many professional athletes, when applied to Black athletes, it takes on added animus. Terms like “ungrateful,” “arrogant” and “disrespectful” become shorthand for the very idea of the Black athlete, whether directed at Jack Johnson more than a century ago or Lebron James. Such comparisons do an injustice to Jackie Robinson.

For several generations of Americans, Robinson was the embodiment of the Black athlete who was grateful for his opportunity to play professional sports. In the minds of those who wished that their favorite Black athletes just “shut up, and play ball,” Robinson became a national treasure. As Malcolm X suggested right after a young Cassius Clay won the heavyweight boxing championship, “Cassius Clay is the finest Negro athlete I have known…He is more than Jackie Robinson, because Robinson is the White man’s hero.” Indeed, in the aftermath of the (momentary) radicalization of Black athletes in the 1960s as exemplified by Jim Brown, Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul Jabbar), Tommy Smith, John Carlos, and Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay), Robinson was an object of nostalgia.

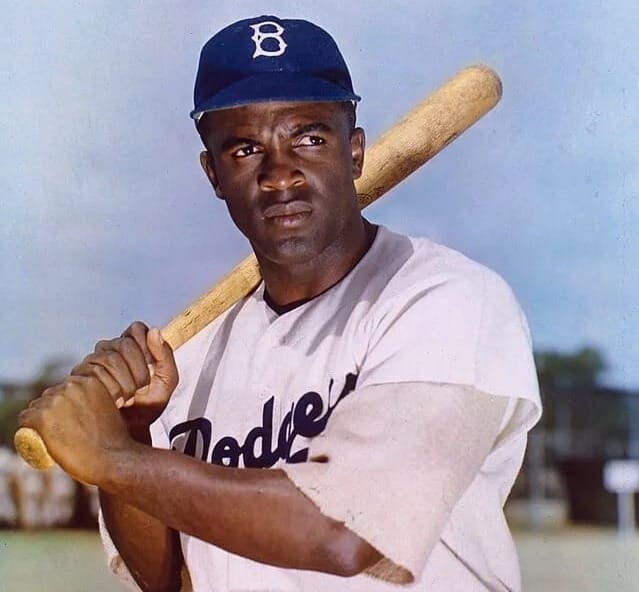

With the image of Robinson gleefully galloping around the bases or stealing home, cemented in the national memory, few could bear witness to the pressures that he faced, or the ways that he fought back against the indignities that he faced. For a player who was known for stealing home, arguably one of the most difficult individual plays in the sport of baseball, in which one must use cunning and guile, it should not be surprising that Robinson might have responded to the racism of the day in ways that went unnoticed by many.

In his well-read tome, The Boys of Summer, Roger Khan recalls an incident with Robinson during a spring training game in New Orleans in 1949. In a nod to Robinson’s drawing power, the owner of the field in New Orleans, loosened his segregation policy, and allowed a group of Blacks to watch the game from the stands. Robinson though, was apparently dismayed when Black fans cheered the police officers who allowed them into the stands, shouting: “don’t cheer those goddamn bastards. Don’t cheer. Keep your fuckin’ mouths shut…Don’t cheer those bastards, you stupid bastards. Take what you got coming. Don’t cheer.”

Robinson seemed to want to make sure that he and those Black fans who entered the stadium that day would never forget the price they had to pay — literally — for the privilege to play and watch a game. Robinson intrinsically understood that there were many more important and difficult battles to wage. The police that those fans cheered that day, would be the same officers directing fire hoses at them and standing in the entrances of soon to be integrated public schools in a few short years.

To be sure, there were likely many such moments of private tirades by Jackie Robinson, besides the one that Kahn was privy to that day in 1949. Willie Mays, arguably the most popular Black ballplayer of the late 1950s and 1960s, recalls that his own relationship with Robinson was tainted. Robinson felt that Mays needed to be more outspoken about the racist insults that were still directed at Black players. Robinson was no militant; a moderate Republican by choice, what angered Robinson most was when hard-work and diligence among Blacks was diminished by mainstream culture. Such was the case when Robinson, a second lieutenant in the Army, faced court martial in 1944 for challenging Jim Crow laws in Texas (Fort Hood).

If Mays was not interested, Robinson found an attentive congregation in some of Mays’ peers — the generation of Black ball players that emerged after Robinson broke the color line. Players like Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, Bob Gibson and later Curt Flood — who was largely responsible for the advent of free agency in professional sports, because he resisted being treated as chattel — embodied a generation of Black baseball players whose sense of pride and justice, and willingness to challenge the status quo in the sport, and to a lesser extent the larger society, literally leveled the playing field.

That sense of pride, justice and history was still on the mind of Barry Bonds, when he emerged as a Baseball superstar in the 1990s. Bonds witnessed firsthand the resentment of his god-father Mays, who came to the realization that he would never be feted the way some of his white peers, like Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle and Ted Williams were — until after their deaths. Bonds had an even more intimate view of his father’s struggles in the sport, as Bobby Bonds’ skill-set — the quintessential five tool player of the 1970s — eroded in concert with his descent into alcoholism. The younger Bonds never forgave journalists for being a source of his father’s anxieties and frustrations, which was manifested in Bonds’ active disdain for the press corps beginning his rookie season with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1986.

Though he was not particularly close to his father, Bonds seemed driven to achieve a level of success that his father was unable to sustain. And though his level of achievement seemed to transcend the animus he generated among the journalists who covered him, Bonds literally shrank in the shadow of the two-headed muscle-bound homerun machine — Sosa and McGuire — who became the faces of the sport in the late 1990s. Bonds’ finely honed skill-set, which made him the logical heir to players like Mays and Mantle before him, was suddenly an afterthought for a nation who desired a sport where “they bang(ed) ’em, where they hang(ed) ‘em.” By all accounts, this is the moment when Bonds’ dance with PEDs first began; Bonds making sure that he would not be forgotten.

Bonds and Ken Griffey, Jr. — linked by their like skills as players and fathers who excelled in the sport — were of the last generation of Black players who could remember the era in which the presence of Black players radically transformed the sport. Griffey, Jr. was not immune to witnessing the slights that came with the racial shifts in the sport; he famously refused to even consider playing for the New York Yankees in response to how Yankee management treated his father. Yet Griffey, Jr., who was known throughout his career as “The Kid” — a clear nod to the boyish charm that Mays presented as the “Say Hey Kid — cultivated a much different relationship with the fans and the sports journalists.

How Griffey, Jr. processed this all — including the criticisms directed at him late in his career for not living up to the expectations placed on him — is likely locked away in those same little boxes that Jackie Robinson had to pack away. The mask that Paul Laurence Dunbar evoked at the end of the 19th century, was the game face that many Black athletes wore at the end of the 20th century. Griffey, Jr. was as adept as any in this regard.

Griffey, Jr. could always take comfort in how highly compensated he was, in ways that were unfathomable for Robinson, and those first two generations of Black baseball players. Surely Bonds could also take comfort in such trinkets of success, but like that private rant that Roger Kahn captured in New Orleans in 1949, Bonds seemed to always want the fans, the press and sport itself, to pay for what he was forced to remember.

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Mark Anthony Neal's work on Medium.