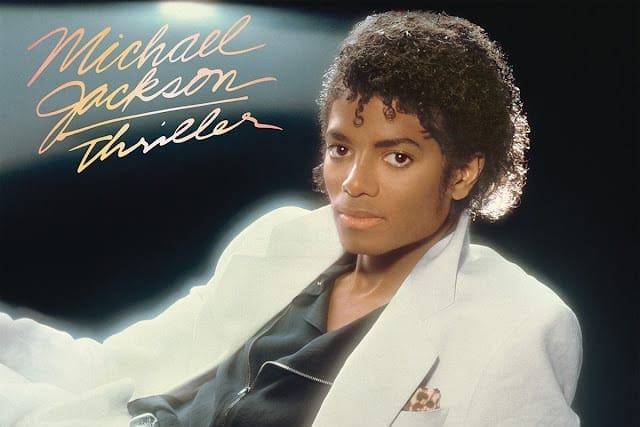

Michael Jackson was fifteen years into a professional singing career when Thriller was released on November 30, 1982, but nearly a decade past his peak years as the boy lead singer of his family group, The Jackson Five. Not yet aged 25, Jackson could have easily become another child-star as cultural footnote — much like his temporal peer Donny Osmond was at the time. And indeed in the years between Jackson’s star-turn as the Scarecrow in The Wiz (1978) — a soulful adaptation of The Wizard of Oz — and the release of Thriller, Jackson worked hard to craft an image of an independently minded adult who, removed from the comforts of his family clan, the assembly-line logic of the Motown label and the overbearing influence of family patriarch Joe Jackson, was now in control of his life and, more importantly, his music. What may have begun as simply a stab at independence, eventually became a stab at history; Thriller remains one of the biggest selling recordings in the history of the music industry.

Critical acclaim for Thriller was immediate. In the pages of the Sunday New York Times (December 19, 1982), John Rockwell wrote that “Thriller is a wonder pop record, the latest statement by one of the great singers in popular music today. It is as hopeful a sign as we have had yet that the destructive barriers that spring up regularly between white and black music — and between whites and blacks –in this culture may be breached once again.” Yes, Michael Jackson as unwitting Race Man. Thriller’s lead single “The Girl is Mine” featured Paul McCartney in what was a calculated appeal for crossover success and pop gravitas, on Jackson’s part. The significance of this collaboration was not lost on critics. In a Newsweek piece titled “The Peter Pan of Pop” (January 10, 1983), Jim Miller noted that the song “sounds very pretty and perfectly innocuous — until you begin to think about the lyrics. Have American radio stations ever before played a song about two men, one black and the other white, quarreling over the same woman?” Recorded a year after McCartney and Stevie Wonder broke barriers with “Ebony & Ivory” and nearly two years to the anniversary of John Lennon ‘s murder, the collaboration with McCartney gave Jackson instant credibility among “serious” pop audiences.

But crossover strategies and MJ's own pop appeal would mean little if not for the sonic landscape that producer Quincy Jones created for Jackson. It was during the filming of the 1978 film The Wiz that Michael Jackson and Quincy Jones, the film’s executive producer, laid the groundwork for the productive and profitable professional relationship that transformed Jackson into global pop star. Jones’ brew of sophisticated and subtle pop-jazz — a sound he brilliantly mined on his own albums Body Heat (1974), Sounds…And Stuff Like That (1978) and the award-winning The Dude (1981) — provided Jackson with a mature, yet youthful style. Jackson and Jones initially collaborated on Jackson’s Off the Wall (1979) — arguably the best album in Jackson’s oeuvre — creating signature pop confections like “Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough”, “Rock with You” and the title track.

Though Jones might have helped Jackson to sound grown-up, Jackson’s naivete helped ingratiate him to audiences. In the aforementioned Newsweek article Quincy Jones describes Jackson as having a “balance between the wisdom of a 60-year-old” — not surprising for a young man who had worked intimately with Berry Gordy, Kenneth Gamble, Leon Huff and Jones — “and the enthusiasm of a child.” Jackson’s childlike demeanor (the soft voice) and somewhat androgynous (and Jerri-curled) features made him user friendly for a generation of American and later global children, who viewed Jackson as a Peter Pan figure. Jackson played off on his child-like sensibilities most brilliantly in the video for the title track. “Thriller” was the fourth release (a year after the initial release) from the project and featured a cameo by the late Vincent Price. Written by Rod Temperton, who penned songs on both Thriller and Off the Wall, “Thriller” was recorded as a tribute to Jackson’s love of horror movies. Employing the talents of veteran film director John Landis (American Werewolf in London and Trading Places) Jackson created the first “music video as event” — a half-hour long film short that directly referenced Night of the Living Dead (1968) and a host of other horror flicks.

Thriller’s success owed as much to Jones’s production as it was Jackson’s desire for cinematic presentations of his music. With each music video beginning with “Billie Jean” and then “Beat It”, Jackson upped the artistic ante — these were postmodern spectacles in a form of presentation that was still grappling with its own possibilities. Jackson’s seamless presentation of (musical) text and image was cutting edge and spoke powerfully to the historic relationship between blackness and technology — indeed Black bodies were often literally the technology that cut the edge. Decades later it’s difficult to hear Jackson’s “hee, hee, hee” over Paul Jackson’s signature baseline on “Billie Jean” and not envision the “Blade Runner” style video that was shot in support of the song. That said, I still argue that the purest form of genius on the Thriller is the opening track “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’”.

“Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” marries Jackson’s boyish exuberance with a complex rhythmic structure that propels the song into an ethereal exorcism of funk. As the song rumbles towards its close, Jackson seemingly summons the gods, delivering a sermonic spectacle worthy of the greatest Black preachers (“Lift your head of high and scream out to the world / I know I am someone and let the truth unfurl / No one can hurt you now, because you know what’s true / Yes I believe in me, So you believe in me”). The song soars when Jackson yelps (literally, out of breath) “help me sing it” at which point the legendary backing group The Waters (Julia, Maxine and Oren) chime in rhythmically “ma, ma, se, ma, ma, sa, ma, ma coo, sa.” These utterances were appropriated from Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango’s classic “Soul Makossa” (1973). Jackson ad-libs behind the Waters when suddenly the bottom drops out, and listeners are left with Jackson (damn near orgasmic), the still frenzied Waters, the punctuating lines of the horn section (including veteran studio trumpeter Jerry Hey), and a shout-clap rhythm worthy of the Ring Dance tradition that survived the Middle Passage. These are the most brilliant moments on Thriller and moments that most casual listeners of Jackson’s music continue to miss. For those who read Jackson’s ever devolving facial features as some evidence of racial self-hatred, “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” is Jackson’s unspoken retort, as he summoned the Orishas in a way never experienced in American pop music.

***

Time has been hard on our memories of Michael Jackson; both the Jackson who initially stole our hearts as the little Black boy from Gary, Indiana and the Jackson whose sophisticated crossover style, bespoke all the possibilities of a post-Civil Rights world. Thriller is testament to an icon whose current legacy has little to do with the music he created for much of his life. In that regard, Jackson has many peers, including the two men, James Brown and Elvis Presley, who inspired his most spectacular performances — they all have lost their sheen as the years have passed. Nevertheless, Thriller was a singular achievement — one that Jackson spent years trying to recreate. Michael Jackson was never again the pop phenomenon he was at the peak of his fame in the mid-1980s and unfortunately, he never really allowed himself to exhale — deeply — and enjoy the resonances of what was truly a peerless genius.

Mark Anthony Neal is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of African American Studies and Professor of English and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies at Duke University. The author of several books including Looking for Leroy: Illegible Black Masculinities and Black Ephemera: The Crisis and Challenge of the Musical Archive, both from NYU Press. His next book Save a Seat for Me: Meditations on Black Masculinity and Fatherhood will be published by Simon & Schuster.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Mark Anthony Neal's work on Medium.