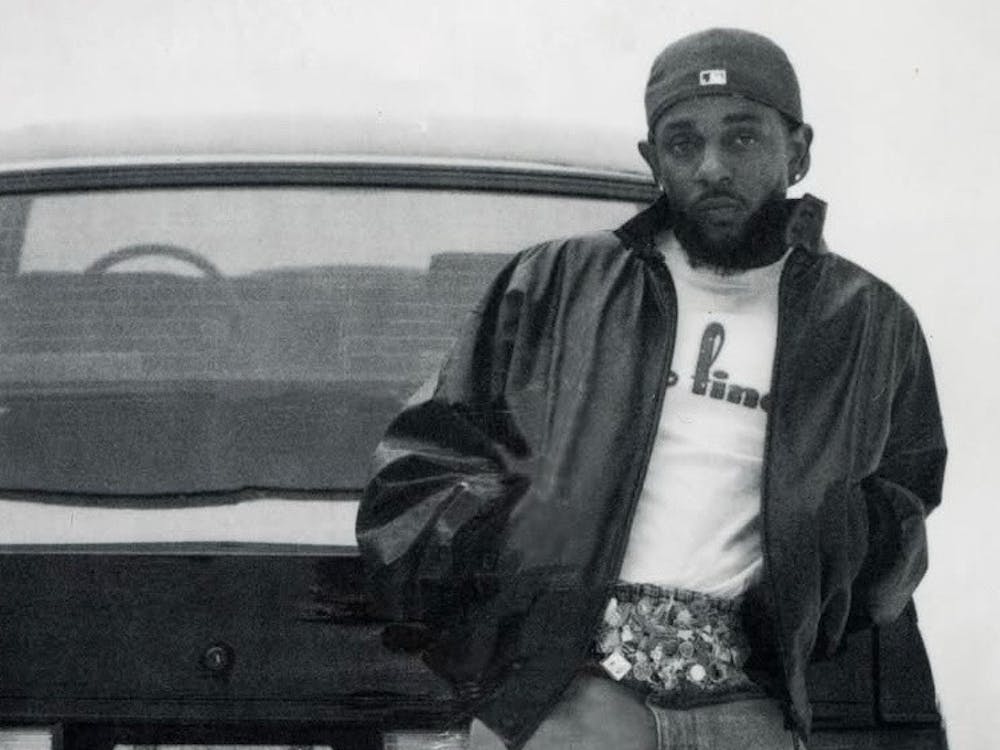

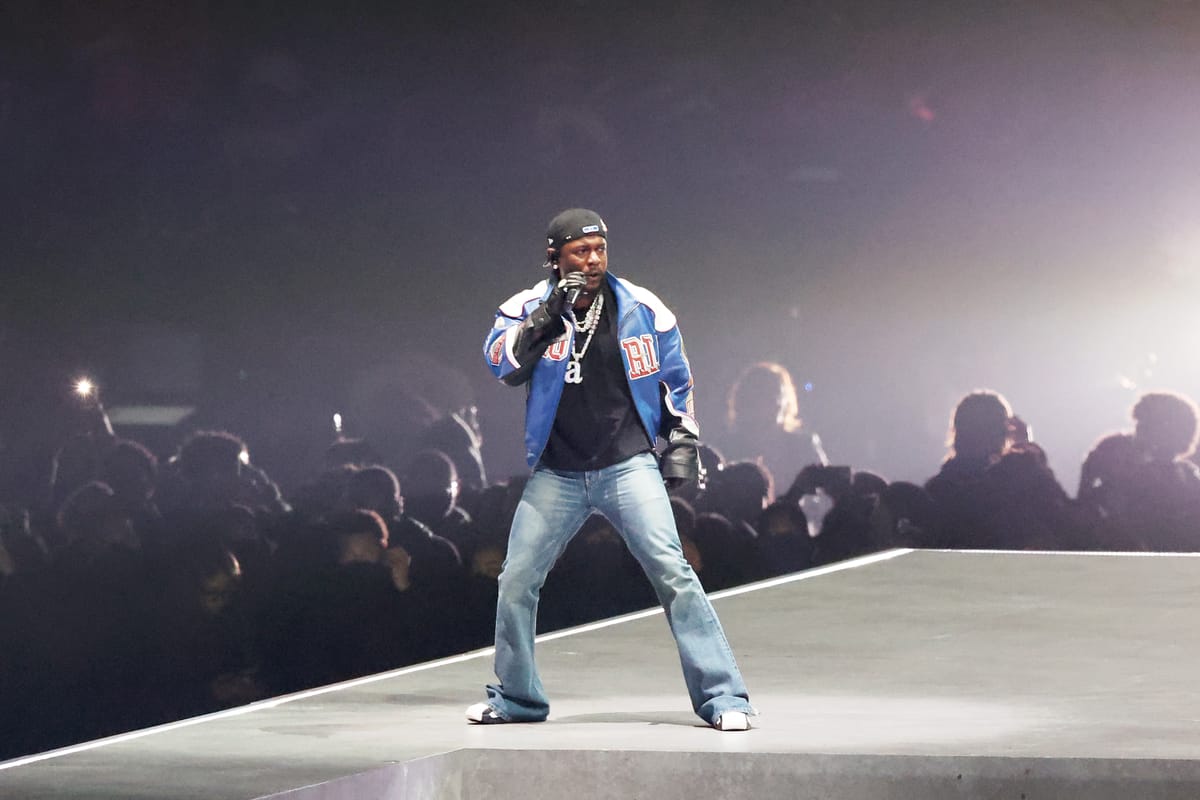

Why does the mere presentation of black culture provoke anger and disdain? Those accustomed to privilege see inclusion as a form of oppression. Take, for instance, the backlash to Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl LIX halftime show. The Pulitzer and Grammy-award-winning hip-hop artist performed as the headliner. An array of Black singers, dancers, and surprise guests accompanied him. It’s become the most-watched U.S. broadcast since the moon landing in 1969. This surpasses viewership for Michael Jackson, the King of Pop’s half-time performance in 1993. Despite its popularity, some people feel triggered when black culture takes center stage.

Rich Tsai, a Republican politician, complained that “not a single white person” performed. Playing the “black national anthem” upset Shelby Alexander, a white woman from Pennsylvania. “The Super Bowl halftime show was so black it would leave fingerprints on coal,” a woman named Susan said. She also felt angry that “not a single Caucasian” performed during the halftime show. The NFL set the tone with their decision to remove the “end racism” sign from the field. As a result, some expected to see fewer Black performers. These comments read like satire, given the stiff conservative resistance to DEI. If you value inclusion, then why attack these policies at every turn? And if you don’t, why complain about an all-Black halftime show? By the way, a Grammy-award-winning artist performing is not evidence of preferential treatment. But that didn’t stop Jack Posobiec, a far-right activist, from calling this a “DEI halftime show.” Among some Americans, the acronym has become a slur—a way to diminish Black people's right to exist.

The irony wasn’t lost on the black community that Kendrick Lamar anticipated their resistance. He seemed to weave their predictable backlash into the narrative. A Black “Uncle Sam,” played by none other than Samuel Jackson, served as the antagonist. He wore a red vest, dark blue suit, a starred bowtie, and a top hat adorned with stars and red and white stripes. After Lamar performed Squabble Up, Uncle Sam said it was “too loud, too reckless,” and “too ghetto.” This is a standard line of attack on black culture from the far right. Given his song choice, he questions whether Lamar “really knows how to play the game.” Uncle Sam expects Kendrick, and by extension all Black people, to play the “great American game.” They follow all the rules, even though they’re often deprived of the benefit of doing so. The imagery of the game controller symbols is a reminder of this.

“The revolution is about to be televised,” Lamar said, preparing the audience. He referenced Gil Scott-Heron’s 1971 song, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised. Corporate interests typically limit TV’s potential for empowering working-class people. Heron’s song suggests citizens cannot sit idly by and await news of a revolution. If they want the world to change, they should become active participants. This much is still true. Yet, in citing his work, Lamar indicates he’s unwilling to play by those same rules—the one where your platform is contingent upon capitulation. Using the most prominent stage to celebrate hip-hop, an art form often scorned and rarely appreciated in America, illustrates that point. Dancers wore red, white, and blue, forming a divided American flag. This imagery seemed to mirror our cultural and political divide. “America was built off the backs of Black people,” we’re reminded as their backs remain bent.

After rapping under a street light on stage, surrounded by Black men, Uncle Sam interjects. “See, you brought your homeboys with you… the old cultural cheat code.” Here, we see black unity threatens the status quo. Black people are accused of cheating the game by sticking together. “Scorekeeper, deduct one life,” Uncle Sam says. This symbolizes the punishment Black people face for breaking the rules of the game, often through state-sanctioned violence. A quartet of Black singers wearing white jean outfits and half-red and black hair joined the set. Kendricks tells them, “I want to perform their favorite song. But, you know they love to sue.” The Canadian rapper Drake filed a lawsuit against Universal for promoting Not Like Us. Just as the beat started to play, Uncle Sam responded, “You done lost your mind.” The implication here is that Kendrick Lamar shouldn’t perform the song. That he should self-censor because that’s part of playing the American game.

Uncle Sam responded approvingly when Kendrick Lamar played All The Stars with SZA, a track that became a commercial success on the Black Panther movie soundtrack. “That’s what America wants. Nice and Calm. Don’t mess this up,” he warns. Of course, Kendrick Lamar eventually does press the red button. As the beat for Not Like Us began to play, the quartet of women asked, “Are you really bout to do it.” He responds, “40 acres and a mule. This is bigger than the music.” When they ask him again, he responds, “They tried to rig the game, but you can’t fake influence.”

“40 Acres and Mule” references Field Order №15 issued by Major General W.T. Sherman on January 16, 1865. This document publicized a plan to provide restitution to newly freed Black people. The federal government promised them land. “The islands of Charleston South,” along with “the abandoned rice fields that bordered “The St. Johns River, Florida,” would be “reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the Proclamation of the President of the United States.” Some Black people received land under this agreement. Sadly, under President Andrew Johnson, the federal government quickly changed course. Black families that did resettle were forced to leave and give the property back to White people. This broken promise deprived Black Americans of the opportunities extended to others.

While some responded with outrage to black culture, others, like writer Helen Cassidy, expressed appreciation for what they learned from the performance. In a viral post on TikTok, she noted that Kendrick Lamar’s “40 Acres and a Mule line is particularly potent.” She remembered first hearing about the topic while attending school in the Bronx. But has since brushed up on the subject. “It would help them with a headstart,” she said of the federal government’s initial reparations plan. Though, she noted, “as with many of the promises made to Native Americans,” the federal government did not follow through. “I never really equated 40 acres and a mule because it’s not something that really ever touched my life,” she confessed.

Yet, the performance jogged her memory, allowing her to consider the topic anew. “I never really equated it to… the [1862] Homestead Act” before, Cassidy shared. The federal government offered 160 acres of free land to those willing to farm on the land and cultivate it. This program helped many White families build generational wealth. Yet, racist policies prohibited Black people from receiving these same land grants. How tragic that the 40 acres the federal government deprived Black Americans of was given three times over to White people. Even those who had recently immigrated to the country. Atlantic writer Vann R. Newkirk II noted that “Black Americans have lost approximately 12 million acres of land.” Mass land dispossession affected 98 percent of Black farmers. This “war waged by deed of title,” he noted, “can only be called theft.” Today, White households have 10 times more wealth than Black households. Such a racial disparity explains why many Black people feel the game is rigged against them.

Some people feel angry when black culture takes center stage. That much is clear from some of the responses to the performance. They complain that they feel excluded whenever Black artists have a moment to shine. Yet, their complaints overlook how often white people are centered in American society. When you are accustomed to turning on the television and seeing only your culture reflected in entertainment, you may mistake the inclusion of others as oppression, even when it’s not. Instead of appreciating Kendrick Lamar’s performance and unraveling the various layers of meaning in the performance, many are seeing red, too blinded by racism to see the big picture.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is edited and republished with author's permission. Read more of Dr. Allison Gaines' work on Medium.